Is the Apostle’s Fast “Easier”?

The Apostle’s asceticism and the “vacation season”

The Apostle’s asceticism and the “vacation season”

The Apostles’ fast goes back to the earliest times of the Christian Church. As we know, it was established when in both Constantinople and Rome, churches were built in honor of the chief apostles Peter and Paul. The sanctification of the Constantinople church was performed on the feast day of these apostles, June 29 (according to the old calendar; that is, July 12 according to the new), and from that time on this day has become particularly solemn in both the East and West. This is the day that the fast ends. It’s beginning is moveable, depending upon the celebration of Pascha; therefore the length of the fast varies from six weeks to a week and a day [if observed according to the Julian Church calendar.—Ed.].

To see the “King”

It would seem that there is nothing unusual about the fast. In the Church calendar, besides the four yearly fasts there is also Wednesday and Friday—the days when we remember the betrayal of the Savior by His disciple and the sufferings, crucifixion, and death on the cross of our Lord. Well, many times I have run into a certain perplexity, if I can call it that, from people in internet space, among the non-religious, or those just beginning their path to the Church, concerning fasts in the summer period. One of these perplexed arguments sounds almost shocking: “But that is the vacation season!” And even, what is interesting, amongst the believing and religious people you might find this view: “Well, the Apostles’ Fast is sort of easier…”

Here of course is the very time to ask the question, “What is so easy about it?”—besides the culinary aspect? But if you are fasting with one eye on the refrigerator then wouldn’t it be simpler to forget the whole thing and take up sports, or find yourself a good dietician and follow his instructions? If the fast days are darkened by the absence of our favorite delicacy then what is the point in thinking about forcing yourself towards the spiritual life? Because in every fast, at any time of the year and even week, the end goal—and the main means—is joy. Joy is overcoming, liberation, leaving the daily vanity, discovering yourself, even if it’s not the prettiest sight. The fast strips a person; it doesn’t tear his clothing off but pushes him away from ambition and self-reliance, illusion and self-deception, as if suggesting, “You have covered yourself with what is futile, you have wrapped yourself with what is unnecessary, but just look, take an honest look at yourself… It’s all like in the fairy tale—the emperor is naked!”

Peter is the rock in the foundation

The fast is a wake up call on the soul’s long journey on earthly paths towards Heaven. It is a chance to jump out of the endless parade of masquerades and carnivals of carelessness; it is the ability to feel pain in order to understand why and how to cure it.

The Apostles’ fast is in this sense no exception. When Apostles’ fast begins I remember the Savior’s words: But the days will come, when the bridegroom shall be taken from them, and then shall they fast (Matt. (9:15); and also the words of the apostle Paul about those whose lives were spent in weariness and painfulness, in watchings often, in hunger and thirst, in fastings often (2 Cor. 11:27). After all, in ascending to the Father, the Savior commanded His disciples to “go and teach”; and could this have been possible without fasting and prayer, without preparing themselves for this difficult, and most often terrifying labor? For more than three centuries, preaching the Kingdom of God was met by the world with rage and opposition. And why only say, then? Even today the remembrance of Christ causes this world discomfort and irritation, although you would think that times have changed.

But why the Apostles’ Fast? Why not the Peter and Paul Fast? That would have been logical, since we celebrate the feast of these two apostles at the end of the fast. Possibly it is because the apostle Peter was amongst the first disciples of Christ, His witness and travelling companion; perhaps because the most onerous trial—public denial but then repentance and ascetic labor of preaching and suffering for his Teacher—fell precisely to the apostle Peter’s lot. After all, the Lord in one of His meetings after His Resurrection indicates to Peter that his life would not end in peace and comfortable old age, but in sufferings and death for the Good News. And the Lord Himself in this meeting restores Cephas, that is, Peter, to his apostolic dignity. As the apostle Peter denied the Savior thrice, so does he promise three times to have faith and love for his Lord, becoming an unshakeable rock upon which the Lord’s Church would be built.

Paul—from Damascus to Rome

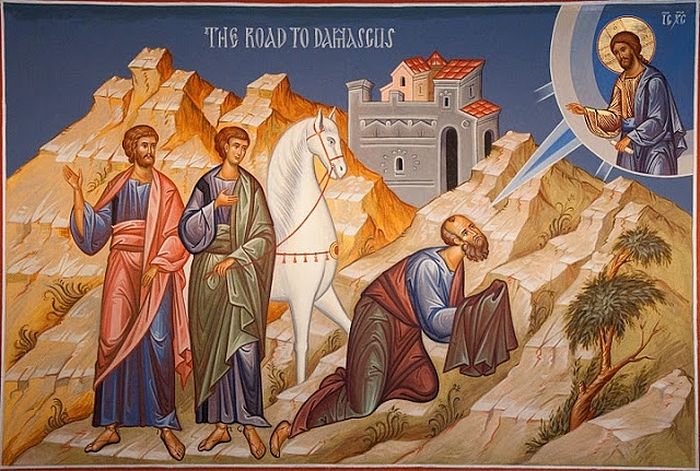

At the same time, we can’t but recall also the apostle Paul, and that their lives were so different, as they themselves were different—even in those times, when they were both faithful and zealous preachers of God’s words. Paul was the son of wealthy and upper class parents, a Roman citizen, the disciple of the famous Jewish teacher of the law Gamaliel, “a scribe and a Pharisee.” Paul was a terrible foe to Christians, fomenting hatred for Christians and asking the Sanhedrin for permission to chase down Christians everywhere and bring them to Jerusalem in bonds. And Paul, furiously resisting the Lord’s truth, afterward just as fervently believed. On the road to Damascus the future apostle would hear God’s voice, physically feel his blindness, and then gain spiritual sight. Thus did the Lord wreak the great miracle of converting an enemy into a zealous servant and preacher. In the New Testament, most of the Epistles are written by the apostle Paul; and the Acts of the Apostles tell us of the travels, sorrows, and hardships that Apostle Paul had to endure. Finally, the life of the apostle Paul, just like that of Peter, ends in martyrdom, cut down by the sword in the Eternal City, of which Paul was a citizen. Not all roads lead to Rome, but the blood of the apostles Peter and Paul are testimony in the city where God’s truth was most furiously rejected, and their deaths became a triumph over death and spiritual emptiness.

The Fast is a time of emulation

The apostles Peter and Paul are the greatest examples of spiritual steadfastness and reason. Faithfulness and knowledge, simplicity and inspired words—aren’t they the main qualities that all of us Christians are called to have in the preaching of the Gospel, salvation, and eternal life with God? When divine services are held in the churches for one or another of the apostles, at a certain moment we sing the magnification for that saint in which are the words: “And we honor thy pains and labors, whereby thou didst labor in proclaiming the Gospel of Christ.” That is, in other words, although the apostles’ labors were difficult and accompanied by many sorrows and depravations, the Savior never abandoned any on His disciples and gave them spiritual joy and the grace of the Holy Spirit, sent down on the day of Pentecost.

And if we look at the Church calendar, we see that the Apostle’s Fast begins soon after the feast of Pentecost, Holy Trinity Day. It begins as a reminder to us that in our lives we should at least in some measure emulate Christ’s disciples. Not repeat their labors to the last detail, but at least by our actions, our lives and faith we should manifest to our friends and family the light of Christ, the life and grace of His Church, which was established on the rock and foundation of apostolic faith, on the confession and martyrdom for Christ’s name, on the faithfulness and purity of the lives of Christians in those times. They were difficult and sorrowful times.

None of the twelve apostles other than the apostle John the Theologian died a natural death, no one peacefully reposed surrounded by family, but their labors were built upon fasting and prayer, without regard for the time of year or season of vacations. Moreover, Christ’s preachers’ fasting and praying was not limited to dates showing “from” and “to”, like our fasts are. The preaching of God’s Word throughout the world is the triumph and beginning of the victorious news of God’s soon coming in glory and grandeur, in the power and light of Truth, of the final triumph of the Kingdom of God. And far from many in our world understood or received this news. The desire to change our lives, to become different cannot be something in and of itself. It is impossible to wake up on Monday and just become a religious Christian. Changes often occur very painfully in people. Peter learned of the bitterness of his own pride on the night when the cock crowed thrice, and Paul blinded by fury and wrath against Christians saw himself in all his sinfulness and blindness on the road to Damascus. But the Lord saw both of their hearts, and He not only accepted their repentance, but manifested their glory in great deeds and ascetic labors.

When an embrace is more important…

There is a remarkable iconographic image of the apostles Peter and Paul where they are depicted in an embrace. This depiction is remarkable in that in the lives of these apostles, their relationship was rather complex. They truly were quite different from each other, and besides that, the apostle Peter viewed Paul with suspicion for quite some time, because he knew what he had been before. All of these human asperities were covered and smoothed out by the most important thing—oneness of mind in the faith and the preaching of Christ. Neither was it mere coincidence that they both received a martyr’s crown in the same place—Rome. And the symbolic embrace on the icon is a reminder to all of us that only in Christ can we be truly united, that everything else is secondary, that our relationships, difference of views and interests cannot be higher than the most important thing—our witness of the Savior to the world.

Perhaps the fast is given to us also in order that in recognizing who we are and why we are in this world, we might share this with others. After all, the fast is a journey of the soul.

And we all are on this journey.

From the periodical Saratovskaya Panorama No. 22 (1103).

Priest Andrei Miziuk

Translation by Nun Cornelia (Rees)

Orthodoxy and Modernity