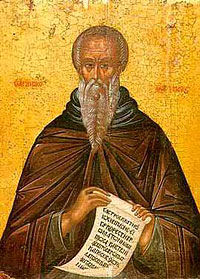

St. John of the Ladder (Climacus)

St. John Climacus is honored by the Church as a great ascetic and as the author of a remarkable work entitled, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, and therefore he has been named “Climacus,” or “of the Ladder.”

St. John Climacus is honored by the Church as a great ascetic and as the author of a remarkable work entitled, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, and therefore he has been named “Climacus,” or “of the Ladder.”

There has been very little information preserved about his origin. Tradition tells us that he was born in around the year 570, and was the son of Sts. Xenophon and Maria, who are commemorated on January 26/February 28. St. John came to the monastery on Mt. Sinai at age sixteen. Abba Martyrius became his spiritual father and mentor. After four years of living on Mt. Sinai, John was tonsured a monk. One of the fathers present at his tonsure foretold that John would become a great luminary of Christ's Church. St. John labored in asceticism for nineteen years in obedience to his spiritual father. After the death of Abba Martyrius, St. John chose the life of reclusion, departing to a desert place called Thola, where he lived forty years in silence, fasting, prayer, and repentant tears. It is not by chance that St. John speaks so much of repentant tears in The Ladder. "As fire burns and destroys dead wood, so do pure tears cleanse all impurity, both inwardly and outwardly." His prayer was strong and effective—this can be seen in the following example of the great ascetic's life.

St. John had a disciple, Monk Moses. One day St. John sent his disciple to spread soil on the garden beds. As he was fulfilling his obedience, Monk Moses became weary from the fierce summer heat and reclined under the shade of a large cliff. St. John was in his cell at that moment, resting a bit after his labor of prayer. Suddenly a man of venerable countenance appeared and woke the ascetic, reproofing him: "John, why are you resting peacefully here while Moses is in danger?" St. John immediately arose and began praying for his disciple. When Moses returned that evening, the saint asked him if anything had happened to him that day. The monk answered, "No, but I was in serious danger. A large rock broke off from a cliff under which I had fallen asleep at midday and nearly crushed me. Fortunately I was having a dream in which you were calling me, and I jumped up and ran; at that moment a huge rock fell with a crash upon that very place where I was…"

It is known from St. John's life that he ate what was allowed by the rule of fasting, but within measure. He did not go without sleep at night, although he never slept more than was needed to support his strength for ceaseless vigilance, and so as not to negatively affect his mind. "I did not fast beyond measure," he said of himself, "and I did not conduct intensified night vigil, nor did I sleep on the ground; but I humbled myself…, and the Lord speedily saved me." The following example of St. John's humility is notable. Gifted with a strong, sharp mind that was made wise by deep spiritual experience, he taught everyone who came to him and guided them to salvation. But when certain others out of jealousy accused him of loquaciousness, which they said sprung from vainglory, St. John took a vow of silence in order not to temp anyone, and remained thus for a year. His enviers admitted their error and begged the ascetic not to deprive them of his beneficial instruction.

To hide his ascetic labors from people, St. John would sometimes depart to a solitary cave, but fame of his holiness spread far beyond his enclosure, and people from all walks of life would come to him seeking a word of edification and salvation. When he was seventy-five years old, after forty years of ascetic labors in solitude, the saint was chosen to be abbot of Sinai. St. John Climacus ruled the holy monastery for four years. The Lord granted the saint many gifts of grace toward the end of his life, including clairvoyance and miracle-working.

During St. John's abbacy, another St. John, abbot of Raithu Monastery (commemorated on the Saturday of Cheesefare week) asked him to write the famous Ladder—instructions for the ascent to spiritual perfection. Knowing of the saint's wisdom and spiritual gifts, the abbot of Raithu asked on behalf of all the monks of his monastery for "true instruction for those who seek unwaveringly, and a kind of steadfast ladder that will take those who desire it to the Heavenly gates…" St. John, who had a humble opinion of himself, first balked at the task but then set about writing the treatise out of obedience to the request of the Raithu monks. He thus called the work, The Ladder, explaining his choice: "I have built a ladder of ascent… from earth to holiness… In honor of the thirty years of the Lord, I have built a ladder of thirty steps, which if we climb it to the age of the Lord, we will be righteous and safe from falls." The aim of this treatise was to teach us that the attainment of salvation requires difficult self-denial and intense ascetical labor. The Ladder first suggests the cleansing of sinful impurity, the uprooting of vices and passions of the "old man"; second, it shows the restoration of God's image in man. Although the book was written for monks, any Christian who lives in the world will find it a reliable guide on the ascent to God. Pillars of spiritual life such as St. Theodore the Studite, St. Sergius of Radonezh, St. Joseph of Volokolamsk, and others continually referred to The Ladder as the best book for soul-saving instruction.

The content of one of the steps of The Ladder (No. 22) discusses the labor of uprooting vainglory. St. John writes,

Like the sun, which shines on all alike, vainglory beams on every occupation. What I mean is this: I fast, and turn vainglorious. I stop fasting so that I will draw no attention to myself, and I become vainglorious over my prudence. I dress well or badly, and am vainglorious in either case. I talk or I remain silent, and each time I am defeated. No matter how I shed this prickly thing, a spike remains to stand up against me.

A vainglorious man is a believing idolater. Apparently honoring God, he actually is out to please not God but men. To be a showoff is to be vainglorious. The fast of such a man is unrewarded and his prayer futile, since he is practicing both to win praise. A vainglorious ascetic doubly cheats himself, wearying his body and getting no reward.…

The Lord frequently hides from us even the perfections we have obtained. But the man who praises us, or, rather, who misleads us, opens our eyes with his words and once our eyes are opened, our treasures vanish.

The flatterer is a servant of the devils, a teacher of pride, the destroyer of contrition, a ruiner of virtues, a perverse guide. The prophet says, Those who honor you deceive you (Isa. 3:12).

Men of high spirit endure offense nobly and willingly. But only the holy and the saintly can pass unscathed through praise.…

No one knows the thoughts of a man except the spirit within him (cf. 1 Cor. 2:11). Hence, those who want to praise us to our face should be ashamed and silent.

When you hear that your neighbor or your friend has denounced you behind your back or indeed in your presence, show him love and try to compliment him.

It is a great achievement to shrug the praise of men off one's soul. Greater still is to reject the praise of demons.

It is not the self-critical who reveals his humility (for does not everyone have somehow to put up with himself?). Rather it is the man who continues to love the person who has criticized him….

Our neighbor is moved by nothing so much as by a sincere and humble way of talking and of behaving. It is an example and a spur to others never to become proud. And there is nothing to equal the benefit of this….

The Lord often humbles the vainglorious by causing some dishonor to befall them. And indeed the first step in overcoming vainglory is to remain silent and to accept dishonor gladly. The middle stage is to restrain every act of vainglory while it is still in thought. The end—if one may talk of an end to an abyss—is to be able to accept humiliation before others without actually feeling it….

When those who praise us, or, rather, those who lead us astray, begin to exalt us, we should briefly remember the multitude of our sins, and in this way, we will discover that we do not deserve whatever is said or done in our honor.

This and other sayings that we can find in The Ladder serve as an example of that holy zeal for our salvation that is necessary to everyone who wishes live a pious life; and this written treatise, which is the fruit of abundant and subtle observation over his own soul along with very deep spiritual experience, is a great benefit and guide along the path of truth and goodness.

The steps of The Ladder are the ascent from strength to strength on the human path to perfection, which can only be attained gradually and not suddenly; for, in the words of the Savior, The Kingdom of Heaven suffereth violence, and the violent take it by force (Mt. 11:12).