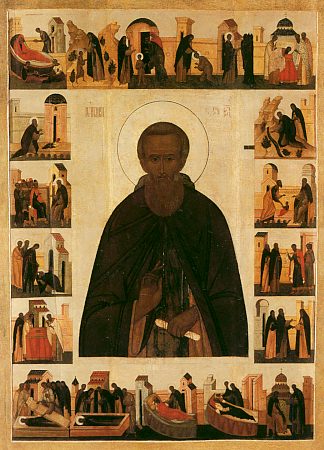

Sergei of Radonezh, Saint of All Russia

The name St. Sergius of Radonezh reminds us of the heights to which our (Russian) land, enlightened by the Word of Christ, is capable of rising. A man who did not write a single book, stands at the beginning of Russian culture of the Muscovite period, and opens the door which leads from a the forested wilderness north of Moscow to the depth of Divine wisdom, to all the mysteries of man and the world. His work is seen to be even more wondrous because we cannot separate in it the fruits of heavenly assistance and the fruits of his own labors. St. Sergius tried all his life to leave the world; he tried not to take upon himself responsibility for the fate of those around him, not to interfere of his own will in the events going on around him. Nevertheless, all the everyday and historical details of that era are so closely interwoven in his life that it would seem that there is no side of Russian life in the latter half of the fourteenth century that he did not sanctify, or where there is no trace remaining of his caring, protective blessing. If we recall what it was like during his time, it becomes clear that St. Sergius stands not only at the beginning of Russian Enlightenment, but is also a symbol of the Russian Renaissance in the most exalted meaning of the word.

The name St. Sergius of Radonezh reminds us of the heights to which our (Russian) land, enlightened by the Word of Christ, is capable of rising. A man who did not write a single book, stands at the beginning of Russian culture of the Muscovite period, and opens the door which leads from a the forested wilderness north of Moscow to the depth of Divine wisdom, to all the mysteries of man and the world. His work is seen to be even more wondrous because we cannot separate in it the fruits of heavenly assistance and the fruits of his own labors. St. Sergius tried all his life to leave the world; he tried not to take upon himself responsibility for the fate of those around him, not to interfere of his own will in the events going on around him. Nevertheless, all the everyday and historical details of that era are so closely interwoven in his life that it would seem that there is no side of Russian life in the latter half of the fourteenth century that he did not sanctify, or where there is no trace remaining of his caring, protective blessing. If we recall what it was like during his time, it becomes clear that St. Sergius stands not only at the beginning of Russian Enlightenment, but is also a symbol of the Russian Renaissance in the most exalted meaning of the word.

A dispassionate evaluation of historical events often reveals unexpected things. If you compare medieval Russia with medieval Europe, you see that a renaissance of Russian culture began slightly earlier than in Europe. It is also quite surprising to see that this renaissance had a Christian character. Rus’, which had been ruled by the Tatars for two hundred years, could not preserve its traditions or culture without faith or reliance on the Church. Without faith, it is completely impossible to create anything. Leonardo, Michelangelo, Luther, Machiavelli—all of these “titans” of the European Renaissance were deeply religious people. They believed in God, but also in the complete power of human reason, in the truth of its esthetic sensibility, in the ability of man to create something beautiful, in his right to create and change the world. European Renaissance was as yet very far from rejecting God and being abandoned by Him. It was only preparing to release the Creator of His responsibility for the fate of the world and pass it on to humans. But the heroes who were willing to accept this responsibility had already come of age in Europe. Fortunately, such people were not yet to be found in Russia.

The reality of Russian life from the year 1237 did not incline people there toward flights of spirit. The price of an individual human under the conditions of the Tatar yoke was at an all-time low. Any discussion of the ability of that individual to influence history, to change its course, would probably have evoked bitter, ironic smiles. Neither the least slave nor the Grand Prince could hope to settle even his own fate according to his own will. The prosperity and life of any person in Rus’ depended upon the outcome of rivalry for the Khan’s throne, the good will or despotism of the Horde’s leaders, the fluctuation of prices on the world slave market, the mortality rate of farm animals, or an unforeseen drought in the Great Steppes. Only the Church was free not to recognize the authority of the Horde. Not getting directly involved in the political process, the Church helped people preserve their strength. Before the face of the Khan even princes fell down and bowed, but before God, every man was free. Childish atheism and man-worshipping did not take hold in Russia then, not because Russia was backward, but because refusing to patiently carry one’s cross meant truly slavish dependence upon the nomadic warrior’s whip. It was impossible for people to throw off that yoke. Hope in God gave them not only hope in salvation beyond the grave, but also in a firm foundation for earthly statehood and domestic constructiveness—because anyone who desires to be saved in the future life should have “labored for God” and “endured to the end” all the oppression of the present life. St. Sergius’ whole life was the fruit of such work and patience.

His Life, written with remarkable tenderness and liveliness by Epiphanius the Wise, gives us the key to understanding the many secrets of Russian culture and the Russian intelligentsia. From the very beginning of his life, even before his earthly birth, Sergius (before monasticism, Bartholomew) was marked with heavenly signs. He cried out three times during the Liturgy while still in his mother’s womb, refused to take his mother’s breast on fast days, or accept milk from a nurse. His parents were clearly aware that a saint has appeared in their family. But it never even entered their heads to exalt their child, or separate him from others because of the talents manifesting in him. The cult of the wunderkind is still something that hardly takes root in the Russian educational tradition even now. Signs, talents, and sanctity itself is given to man from God, and that is why his parents, and after them his biographer, first of all give glory to the Creator, and only then admire the creation. Bartholomew is protected in his childhood, but no more than any parents would cherish every child. He is freed neither from domestic labor, nor from daily obligations, nor from schoolwork.

Observing this education, we see yet another remarkable detail. Any person, even a saint, is not an ideal of earthly perfection. So important a thing for the ascetic as reading and writing he had more trouble assimilating than did his brothers. Everyone around him gently but firmly required him to try harder at school. The saint does not seem to justify their expectations. His life states outright that Bartholomew “did not study diligently” how to read, and “did not listen to his teacher.” Such an attitude towards studies is not approved of, but it was redeemed by the boy’s secret prayer to God. The miraculous fulfillment of this prayer should not lead us to believe that he disdained work (the saint’s whole life is filled with labor). Here we should rather see how God shows equal kindness toward anyone who asks. The saint’s school days, more any other period of his life, disprove any notion about the saint’s superiority over ordinary people. For Russian enlightenment, for Russian culture, the thought of a pre-chosen “spiritual elite” predestined to take authority over and lead the “ignorant people” is altogether foreign. Sergius himself was like the unlearned people, but having received access to wisdom, he never forgot the One to whom it belongs.

Neither did he forget about obedience, the primary virtue of any Christian who is free of self-will. Having already before him a clear life’s goal—monasticism—he nevertheless humbles himself for the sake of his father and mother, remaining at home to take care of them. All those who tend to say that monasticism teaches a person to neglect his family will find in this chapter of his Life an example of how the former proceeds from the latter. Here the saint’s example exhorts us not to shirk our present responsibilities, no matter how important and great our plans might be. A person who is truly religious will never “walk over people” in order to fulfilled his own “lofty” desires, but will to the contrary readily “put the lid on his own desires” in when he sees his neighbor’s need. St. Sergius, whose whole life was a great sacrifice to God, began his podvig with a small sacrifice to his parents; and what is especially important, he did it with joy.

Joyfully also did he set off to realize his life’s work, the comprehension of the Holy Trinity. The philosophical breadth of his work is astounding. The dogma of the Holy Trinity is something very difficult to understand in Christianity. It was not entirely comprehensible to simple people, not only in Kievan Russia and Europe, but even in Byzantium. It is on the subject of teachings about the Holy Trinity that there arose the most serious schisms and heresies in Christianity. The heights of the mystery of the triune Divine Essence should have frightened a man who had such difficulty learning to read. Nevertheless, St. Sergius resolved to penetrate the subject just as decisively as he resolved to leave the world. He then builds his church in the forest and consecrates it together with his brother, even before taking the monastic tonsure. The idea of building a church and the hardest labor falls to him, but he renounces any insolent self will in his search for truth, and waits until his older brother decides to whom the church should be dedicated.

At that moment, the fate of the Russian Church was being decided; even the whole fate of Russian culture was being sealed. Just try to imagine Russia without the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra, without Andrei Rublev, without the churches dedicated to the Holy Trinity. And yet, St. Sergius left that decision up to another, even though he already knew the answer to his own question. Significant here is not only his humility before his elders, but also his inner honesty—something that every researcher must have. Anyone who sets out to study and acquire knowledge of God, man, or the world, does not dare to insist upon his own guesswork without having received some outward confirmation of its truth. Let anyone who thirsts to reveal something to the world first listen to what the world tells him. He that is greatest among you shall be your servant (Mt. 23:11).

This is already another page in the Life of the saint. Having passed through an arduous period of solitary ascetic labors, St. Sergius finds himself faced with the necessity of building a coenobitic monastery. He is most burdened by the necessity of ruling over the brothers, managing the monastery’s domestic affairs, and guiding the monks in their spiritual work. The traditions connected with eldership were almost completely lost by that time in Russia. The abbacy opened to St. Sergius the temptation of occupying his subordinates with jobs that he had never done himself. That is why he was not able to fill the role of abbot without increasing his daily work. Epiphanius writes that the saint “without sloth, served the brothers like a brought slave—he chopped wood for everyone, pounded the grain, milled the flour, baked the bread, prepared the food […]; he cut and sewed clothing and shoes; and he took water from the well in two buckets, carried it on his shoulders up the hill, and placed it at every cell.”

Especially notable is the story about how St. Sergius built a porch for one of the elderly brothers, taking for his day’s work a sifter of moldy bread. This may appear as foolishness to some, but if you recall that there was a famine in the monastery at that time, and the monks were murmuring against the abbot, demanding that he allow them to gather alms, his actions are make sense. The teacher could only teach his students by his own example that bread must be earned by the work of their own hands. This rule remains true up to the present time.

The story of the famine reminds us about yet another of the saint’s character traits—his patience. Furthermore, in it are harmoniously united both labor and prayer, which is an essential part of St. Sergius. He never felt burdened by the troubles and sorrows that visited the monastery. He does not rush to solve them quickly, although he knows that he has the opportunity to do so. He trusts in God to the very end, even when he cannot see any clear meaning of the events. As a result, bread is brought to the monastery by angels, and water springs forth from the very top of a hill. When he returns to the monastery, his older brother contrives a disagreement in the church about rank. The saint distances himself from that argument. He literally departs without trying to answer, not asking the Metropolitan or Prince to intercede on his behalf, and not even asking God to restore justice. After living for a year on the Kirzhach River and founding another monastery, he just as easily returns. It was so hard to disturb his peace that, when a peasant came to the monastery from far away to have a look at the illustrious abbot, yet refuses to recognize Sergius in the tattered old man digging the garden, the saint only affectionately replies, “Do not be sad! God will give you what you seek and desire at once.”

Monasticism disdains the world, but not the people in it. The saint fled human glory, but was friendly to people and quick to help them. To him all were equal—the disconsolate father who brought him his dead son,[2] and the Grand Prince Dimitry, preparing for battle with Mamai. With regard to the battle of Kulikovo, St. Sergius’ political role shows through very distinctly. His blessing upon the Russian forces for the battle imparts a spiritual character to the victory. The soldiers become not only protectors of the Russian land, but also martyrs for the faith. Even the monks take up arms. St. Sergius takes full responsibility for the battle’s outcome, resolutely binding the fate of the Russian Church with the success of the Prince’s campaign. He prays an intercessory prayer for many hours. Then, the battle is won, and the Prince and Metropolitan Alexy beg the saint to receive the rank of bishop, and then metropolitan. But the saint just as resolutely refuses, promising that should they repeat their request, he will depart to the forest, where no one will find him. It is one thing to stand for the truth, but another matter to accept honors.

We cannot neglect to speak of St. Sergius’s material inheritance, the work of his hands. The ring of monasteries that encompassed Moscow and brought light to the wild, northern forests were forged in the Holy Trinity Lavra. The history of each of these monasteries is the history of its founder, often a disciple of the saint, or the student of one of his disciples. A hundred years after the saint’s death, we already see an astounding variety of types of ascetic labor, from St. Joseph of Volokolamsk and St. Paphnuty of Borovsk to St. Nilus of Sora and St. Cyril of White Lake. St. Sergius had a hand in this garden also. The possibility for various spiritual paths toward one and the same goal proves that he founded the in Lavra not a party, or an order, but a brotherhood of Christians, whose main task was to submit not to people or rules written by people, but to God Himself. And like brothers, they are not all alike, but in some subtle way all remind us of their father. St. Sergius determined the common type of Russian sanctity for 400 years to come, and when times had changed completely, his worthy successor became St. Seraphim of Sarov.

In conclusion and in an attempt to determine St. Sergius’s place in the history of Russian culture and enlightenment, I would like to again remind the reader that we have to do not with a scholar, but with a wise man. That means that he is more an example than an authority—an example not only for emulation, but also as a measuring stick. Teaching throughout his life moderation in all things spiritual and earthly, the saint himself became the measuring stick of our culture. His life allows us to test today’s science, art and schools against their heavenly examples. The results of our measurement will perhaps not be consoling, but there is no need to despair. After all—would that every nation were granted such a measure.