The Feast of the Annunciation is one of the earliest Christian feasts, and was already being celebrated in the fourth century.

The Feast of the Annunciation is one of the earliest Christian feasts, and was already being celebrated in the fourth century.

There is a painting of the Annunciation in the catacomb of Priscilla in Rome dating from the second century. The Council of Toledo in 656 mentions the Feast, and the Council in Trullo in 692 says that the Annunciation was celebrated during Great Lent. The Greek and Slavonic names for the Feast may be translated as “good tidings.” This, of course, refers to the Incarnation of the Son of God and the salvation He brings. The background of the Annunciation is found in the Gospel of Saint Luke (1:26-38). The troparion describes this as the “beginning of our salvation, and the revelation of the eternal mystery,” for on this day the Son of God became the Son of Man.

Saint Gregory Dialogus, Pope of Rome, was born in Rome around the year 540. His grandfather was Pope Felix, and his mother Sylvia (November 4) and aunts Tarsilla and Emiliana were also numbered among the saints by the Roman Church. Having received a most excellent secular education, he attained high government positions.

Saint Gregory Dialogus, Pope of Rome, was born in Rome around the year 540. His grandfather was Pope Felix, and his mother Sylvia (November 4) and aunts Tarsilla and Emiliana were also numbered among the saints by the Roman Church. Having received a most excellent secular education, he attained high government positions.

Leading a God-pleasing life, he yearned for monasticism with all his soul. After the death of his father, Saint Gregory used his inheritance to establish six monasteries. At Rome he founded a monastery dedicated to the holy Apostle Andrew the First-Called, where he received monastic tonsure. Later, on a commission of Pope Pelagius II, Saint Gregory lived for a while in Constantinople. There he wrote his Commentary on the Book of Job.

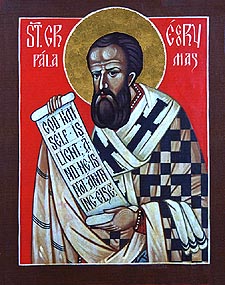

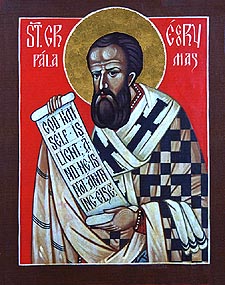

Saint Gregory Palamas, Archbishop of Thessalonica, was born in the year 1296 in Constantinople. Saint Gregory’s father became a prominent dignitary at the court of Andronicus II Paleologos (1282-1328), but he soon died, and Andronicus himself took part in the raising and education of the fatherless boy. Endowed with fine abilities and great diligence, Gregory mastered all the subjects which then comprised the full course of medieval higher education. The emperor hoped that the youth would devote himself to government work. But Gregory, barely twenty years old, withdrew to Mount Athos in the year 1316 (other sources say 1318) and became a novice in the Vatopedi monastery under the guidance of the monastic Elder Saint Nicodemus of Vatopedi (July 11). There he was tonsured and began on the path of asceticism. A year later, the holy Evangelist John the Theologian appeared to him in a vision and promised him his spiritual protection. Gregory’s mother and sisters also became monastics.

Saint Gregory Palamas, Archbishop of Thessalonica, was born in the year 1296 in Constantinople. Saint Gregory’s father became a prominent dignitary at the court of Andronicus II Paleologos (1282-1328), but he soon died, and Andronicus himself took part in the raising and education of the fatherless boy. Endowed with fine abilities and great diligence, Gregory mastered all the subjects which then comprised the full course of medieval higher education. The emperor hoped that the youth would devote himself to government work. But Gregory, barely twenty years old, withdrew to Mount Athos in the year 1316 (other sources say 1318) and became a novice in the Vatopedi monastery under the guidance of the monastic Elder Saint Nicodemus of Vatopedi (July 11). There he was tonsured and began on the path of asceticism. A year later, the holy Evangelist John the Theologian appeared to him in a vision and promised him his spiritual protection. Gregory’s mother and sisters also became monastics.

Life of the Saint

Life of the Saint

This holy, glorious Martyr of Christ came from Amasia in Pontus and was a Roman legionary at the time of Maximian’s great persecution (c. 303). He had been a Christian since childhood but kept his faith secret, not out of cowardice but because he had not yet received a sign from God to present himself for martyrdom. While his cohort was stationed near the town of Euchaïta (Helenopontus), he learned that the people of the district lived in terror of a dreadful dragon, which lurked in the surrounding forest. He realized that here was the quest in which God would show him whether the time had come to offer himself for martyrdom. Going deep into the woods, he came upon an abandoned village whose only remaining occupant, a Christian princess named Eusebia, told him where the monster had its lair. He set off to find it, arming himself with the sign of the Cross, and when he confronted the roaring, fire-spitting beast, he thrust his spear through its head and killed it.

In the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit!

In the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit!

“Forgive me…” Such easy, simple words! It doesn’t even take a deep breath to say them. It took mankind so many generations, tears, sins and so much suffering to respond to the call for repentance by the Holy Prophet and Forerunner John, the Baptist of the Lord, with the words: “Forgive me, O Lord!” and enter the waters of the Jordan.

The Saturdays of commemorations of the dead are called ancestral Saturdays (the first universal commemoration on Meat Fare Saturday, the second, third, and fourth Saturdays of Great Lent, Trinity Saturday, and St. Demetrius Saturday). Why do these take place specifically on Saturdays? What are the historical roots of this tradition? They were not all instituted at the same time.

The Saturdays of commemorations of the dead are called ancestral Saturdays (the first universal commemoration on Meat Fare Saturday, the second, third, and fourth Saturdays of Great Lent, Trinity Saturday, and St. Demetrius Saturday). Why do these take place specifically on Saturdays? What are the historical roots of this tradition? They were not all instituted at the same time.

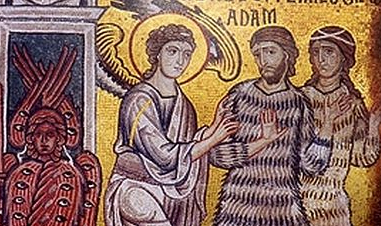

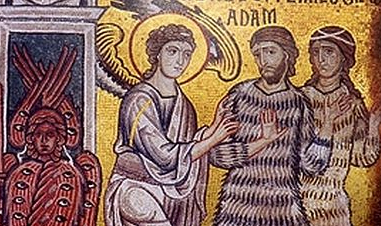

God blessed the seventh day and sanctified it, because in it he ceased from all His works which God began to do (Gen. 2:3). Saturday (Sabbath) for the Jews was a day of festive rest. Christ’s resurrection placed the beginning of the new Israel: a chosen generation, a royal priesthood, an holy nation, a peculiar people; that ye should shew forth the praises of him who hath called you out of darkness into his marvellous light (1 Pet. 2:9). The resurrection day of the Savior of the World became the seventh, festive day that completes the week. Sunday [in Russian, voskresenie, meaning “resurrection”) is a day of prayer in church at Divine Liturgy and pious rest. From a day of earthly rest, Saturday became a symbol of joyous rest in the Kingdom of Heaven: There remaineth therefore a rest to the people of God. For he that is entered into his rest, he also hath ceased from his own works, as God did from his (Heb. 4:9–10). This is where the custom, fixed by the Church typicon, came from of having special services on Saturday for the commemoration of the dead.

The Saturdays of commemorations of the dead are called ancestral Saturdays (the first universal commemoration on Meat Fare Saturday, the second, third, and fourth Saturdays of Great Lent, Trinity Saturday, and St. Demetrius Saturday). Why do these take place specifically on Saturdays? What are the historical roots of this tradition? They were not all instituted at the same time.

The Saturdays of commemorations of the dead are called ancestral Saturdays (the first universal commemoration on Meat Fare Saturday, the second, third, and fourth Saturdays of Great Lent, Trinity Saturday, and St. Demetrius Saturday). Why do these take place specifically on Saturdays? What are the historical roots of this tradition? They were not all instituted at the same time.

The Feast of the Annunciation is one of the earliest Christian feasts, and was already being celebrated in the fourth century.

The Feast of the Annunciation is one of the earliest Christian feasts, and was already being celebrated in the fourth century.  Saint Gregory Dialogus, Pope of Rome, was born in Rome around the year 540. His grandfather was Pope Felix, and his mother Sylvia (November 4) and aunts Tarsilla and Emiliana were also numbered among the saints by the Roman Church. Having received a most excellent secular education, he attained high government positions.

Saint Gregory Dialogus, Pope of Rome, was born in Rome around the year 540. His grandfather was Pope Felix, and his mother Sylvia (November 4) and aunts Tarsilla and Emiliana were also numbered among the saints by the Roman Church. Having received a most excellent secular education, he attained high government positions. Saint Gregory Palamas, Archbishop of Thessalonica, was born in the year 1296 in Constantinople. Saint Gregory’s father became a prominent dignitary at the court of Andronicus II Paleologos (1282-1328), but he soon died, and Andronicus himself took part in the raising and education of the fatherless boy. Endowed with fine abilities and great diligence, Gregory mastered all the subjects which then comprised the full course of medieval higher education. The emperor hoped that the youth would devote himself to government work. But Gregory, barely twenty years old, withdrew to Mount Athos in the year 1316 (other sources say 1318) and became a novice in the Vatopedi monastery under the guidance of the monastic Elder Saint Nicodemus of Vatopedi (July 11). There he was tonsured and began on the path of asceticism. A year later, the holy Evangelist John the Theologian appeared to him in a vision and promised him his spiritual protection. Gregory’s mother and sisters also became monastics.

Saint Gregory Palamas, Archbishop of Thessalonica, was born in the year 1296 in Constantinople. Saint Gregory’s father became a prominent dignitary at the court of Andronicus II Paleologos (1282-1328), but he soon died, and Andronicus himself took part in the raising and education of the fatherless boy. Endowed with fine abilities and great diligence, Gregory mastered all the subjects which then comprised the full course of medieval higher education. The emperor hoped that the youth would devote himself to government work. But Gregory, barely twenty years old, withdrew to Mount Athos in the year 1316 (other sources say 1318) and became a novice in the Vatopedi monastery under the guidance of the monastic Elder Saint Nicodemus of Vatopedi (July 11). There he was tonsured and began on the path of asceticism. A year later, the holy Evangelist John the Theologian appeared to him in a vision and promised him his spiritual protection. Gregory’s mother and sisters also became monastics.

Life of the Saint

Life of the Saint In the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit!

In the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit!