Procopius was born in Jerusalem of a Christian father and a pagan mother. At first his name was Neanias. Following the death of his father, his mother raised her son completely in the spirit of Roman idolatry. When Neanias had grown up, Emperor Diocletian saw him, took a liking to him, and brought him to his palace for military service.

When this wicked emperor began to persecute Christians, he ordered Neanias to go to Al- exandria with a garrison of soldiers in order to exterminate the Christians. But on the way, there happened to Neanias something like that which once happened to Saul. In the third hour of the night there was a strong earthquake and, at that moment, the Lord appeared, and a voice was heard: “Neanias, where art thou going, and against whom art thou rising up?” In great fear, Neanias asked: “Who art Thou, Lord? I am unable to recognize Thee.” Then there appeared in the air an exceedingly luminous cross, as of crystal, and from the cross came the voice: “I am Jesus, the crucified Son of God.” And the Lord further said to him: “By this sign that you have seen, conquer your enemies, and My peace will be with you.”

Commander Neanias’s life was completely changed. He issued an order to make a cross such as he had seen, and instead of going against the Christians, he and his soldiers used their force against the Hagarenes, who were attacking Jerusalem. He entered Jerusalem as a victor, and revealed his Christian faith to his mother. Brought before the court, Neanias removed his commander’s belt and sword, and threw them before the judge, thereby showing that he was a soldier only of Christ the King. After being tortured extensively, he was cast into prison. There the Lord Christ appeared to him again, baptized him, and gave him the name Procopius. One day twelve women appeared before his prison window and said to him: “We too are servants of Christ.” Accused for this, they were thrown into that same prison. St. Procopius taught them the Faith of Christ, and prepared them to receive their “martyr’s crowns.” (This is why St. Procopius, along with the God-crowned Emperor Constantine and Empress Helena, is mentioned in the order of crowning during the wedding ceremony.) Subsequently, the twelve women were brutally tortured. Witnessing their suffer- ing and bravery, the mother of Procopius also came to believe in Christ, and all thirteen were slain.

When St. Procopius was led to the scaffold, he raised his hands toward the east and prayed to God for all the poor, the needy, the orphans and the widows, and especially for the Holy Church, that it would grow and spread, and that Orthodoxy would shine to the end of time. And from heaven it was made known to him that his prayers were heard, after which he joyfully laid his head under the sword and went to his Lord in eternal joy. St. Procopius suffered honorably at Caesarea in Palestine, and was crowned with a wreath of immortal glory, on July 8, 303, and with him Martyrs Theodosia (his mother), tribunes Antiochus and Nicostratus, and twelve women of senatorial rank.

On July 7 the Greek Orthodox Church commemorates the Feast Day of Agia Kyriaki the Great Martyr.

On July 7 the Greek Orthodox Church commemorates the Feast Day of Agia Kyriaki the Great Martyr.

Agia Kyriaki was the only child of Dorotheus and Eusebia. Since she was born on a Sunday (Kyriaki, in Greek), she was named Kyriaki.

One day a wealthy magistrate wished to betroth Kyriaki to his son. Not only was she young and beautiful, but her parents were wealthy, and the magistrate wished to control that wealth. The magistrate went to her parents to request her hand, but Saint Kyriaki told him that she wished to remain a virgin, for she had dedicated herself to Christ.

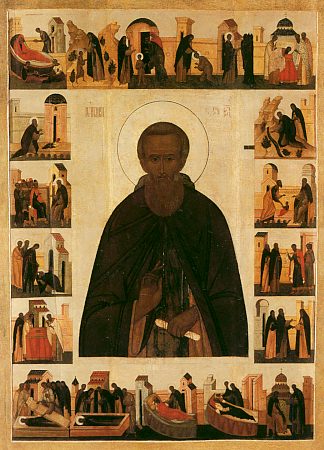

The name St. Sergius of Radonezh reminds us of the heights to which our (Russian) land, enlightened by the Word of Christ, is capable of rising. A man who did not write a single book, stands at the beginning of Russian culture of the Muscovite period, and opens the door which leads from a the forested wilderness north of Moscow to the depth of Divine wisdom, to all the mysteries of man and the world. His work is seen to be even more wondrous because we cannot separate in it the fruits of heavenly assistance and the fruits of his own labors. St. Sergius tried all his life to leave the world; he tried not to take upon himself responsibility for the fate of those around him, not to interfere of his own will in the events going on around him. Nevertheless, all the everyday and historical details of that era are so closely interwoven in his life that it would seem that there is no side of Russian life in the latter half of the fourteenth century that he did not sanctify, or where there is no trace remaining of his caring, protective blessing. If we recall what it was like during his time, it becomes clear that St. Sergius stands not only at the beginning of Russian Enlightenment, but is also a symbol of the Russian Renaissance in the most exalted meaning of the word.

The name St. Sergius of Radonezh reminds us of the heights to which our (Russian) land, enlightened by the Word of Christ, is capable of rising. A man who did not write a single book, stands at the beginning of Russian culture of the Muscovite period, and opens the door which leads from a the forested wilderness north of Moscow to the depth of Divine wisdom, to all the mysteries of man and the world. His work is seen to be even more wondrous because we cannot separate in it the fruits of heavenly assistance and the fruits of his own labors. St. Sergius tried all his life to leave the world; he tried not to take upon himself responsibility for the fate of those around him, not to interfere of his own will in the events going on around him. Nevertheless, all the everyday and historical details of that era are so closely interwoven in his life that it would seem that there is no side of Russian life in the latter half of the fourteenth century that he did not sanctify, or where there is no trace remaining of his caring, protective blessing. If we recall what it was like during his time, it becomes clear that St. Sergius stands not only at the beginning of Russian Enlightenment, but is also a symbol of the Russian Renaissance in the most exalted meaning of the word.

"Sanctity is not just a virtue. It is an attainment of such spiritual heights, that the abundance of God's grace which fills the saint overflows on all who associate with him. Great is the saint's state of bliss in which they dwell contemplating the Glory of God. Being filled with love for God and man, they are responsive to man's needs, interceding before God and helping those who turn to them."

"Sanctity is not just a virtue. It is an attainment of such spiritual heights, that the abundance of God's grace which fills the saint overflows on all who associate with him. Great is the saint's state of bliss in which they dwell contemplating the Glory of God. Being filled with love for God and man, they are responsive to man's needs, interceding before God and helping those who turn to them."

On July 7 the Greek Orthodox Church commemorates the Feast Day of Agia Kyriaki the Great Martyr.

On July 7 the Greek Orthodox Church commemorates the Feast Day of Agia Kyriaki the Great Martyr. The name St. Sergius of Radonezh reminds us of the heights to which our (Russian) land, enlightened by the Word of Christ, is capable of rising. A man who did not write a single book, stands at the beginning of Russian culture of the Muscovite period, and opens the door which leads from a the forested wilderness north of Moscow to the depth of Divine wisdom, to all the mysteries of man and the world. His work is seen to be even more wondrous because we cannot separate in it the fruits of heavenly assistance and the fruits of his own labors. St. Sergius tried all his life to leave the world; he tried not to take upon himself responsibility for the fate of those around him, not to interfere of his own will in the events going on around him. Nevertheless, all the everyday and historical details of that era are so closely interwoven in his life that it would seem that there is no side of Russian life in the latter half of the fourteenth century that he did not sanctify, or where there is no trace remaining of his caring, protective blessing. If we recall what it was like during his time, it becomes clear that St. Sergius stands not only at the beginning of Russian Enlightenment, but is also a symbol of the Russian Renaissance in the most exalted meaning of the word.

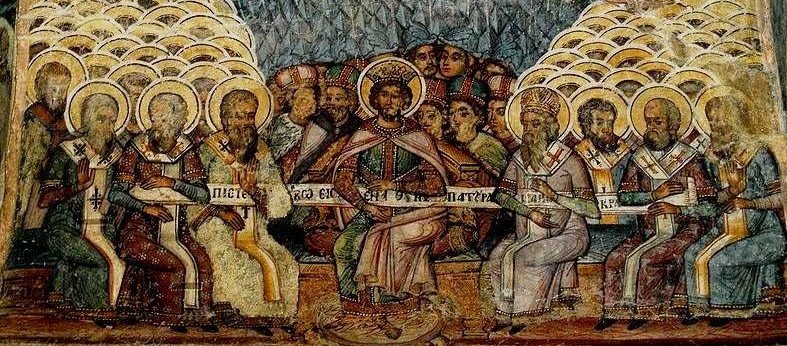

The name St. Sergius of Radonezh reminds us of the heights to which our (Russian) land, enlightened by the Word of Christ, is capable of rising. A man who did not write a single book, stands at the beginning of Russian culture of the Muscovite period, and opens the door which leads from a the forested wilderness north of Moscow to the depth of Divine wisdom, to all the mysteries of man and the world. His work is seen to be even more wondrous because we cannot separate in it the fruits of heavenly assistance and the fruits of his own labors. St. Sergius tried all his life to leave the world; he tried not to take upon himself responsibility for the fate of those around him, not to interfere of his own will in the events going on around him. Nevertheless, all the everyday and historical details of that era are so closely interwoven in his life that it would seem that there is no side of Russian life in the latter half of the fourteenth century that he did not sanctify, or where there is no trace remaining of his caring, protective blessing. If we recall what it was like during his time, it becomes clear that St. Sergius stands not only at the beginning of Russian Enlightenment, but is also a symbol of the Russian Renaissance in the most exalted meaning of the word. On the 31st of May, our Holy Orthodox Christian Church commemorates the First Ecumenical Council and the 318 God-bearing Holy Fathers who participated.

On the 31st of May, our Holy Orthodox Christian Church commemorates the First Ecumenical Council and the 318 God-bearing Holy Fathers who participated.