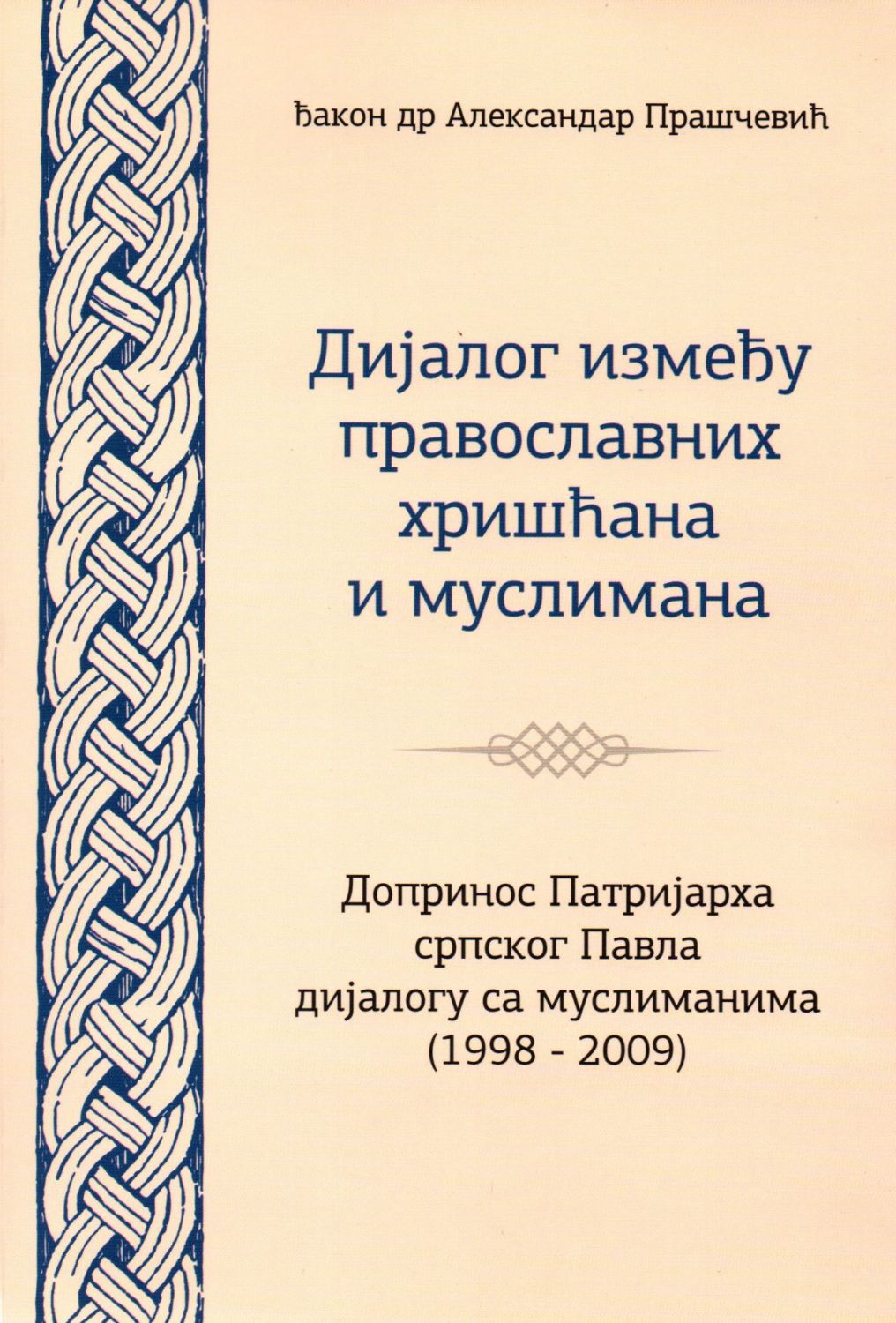

Dialogue between Orthodox Christians and Muslims

Contribution of Serbian Orthodox Patriarch Pavle to the Dialogue with Muslims (1998-2009), Author: Deacon Aleksandar Prascevic, ThD., PhD.

Contribution of Serbian Orthodox Patriarch Pavle to the Dialogue with Muslims (1998-2009), Author: Deacon Aleksandar Prascevic, ThD., PhD.

In the last paragraph of the conclusion in the book on Islam, which is most probably the best book ever written about it by an Orthodox theologian, knowledgeable and wise Archbishop Anastasije (Janulatos), its author said: “Among all living religions, Islam is nearest to Orthodox Christianity, both geographically and spiritually. Regardless of deep theological differences and dramatic conflicts in the past, we share a common cultural and religious ground; an essential mutual understanding of the spiritual heritage of these two worlds presents our duty from which much is expected” (Islam, Belgrade, 2005, p. 259). Patriarch Pavle was deeply aware of the truthfulness of this view and the necessity to respond as Christians to the duty of said mutuality, but he led the Serbian Orthodox Church and cared for its believers at the time of a dramatic conflict with Muslims in the present, and not in the past, which burdened his mission with severe hostilities and hatred surrounding and pressing him from all sides, causing his mind and heart to face excruciating spiritual challenges.

I had numerous opportunities and the good fortune to discuss about Islam and Muslims with our late Patriarch on several occasions, in which he was quietly but earnestly and vividly interested. I particularly remember one of such discussions in Sremska Mitrovica in October 2004, on the occasion of the consecration of the place of suffering of the Sirmium Martyrs on the Sava River, of two icons of Saint Anastasia, one Orthodox and the other Catholic, as a symbol of Pan Christian prayer appeal for peace in the blood-stained territory of the former Yugoslavia. While speaking, Patriarch let himself sigh: “If only Muslims had any icons, to bless them together, for the sake of conciliation and love... However, they do not know of icons, they only have the Quran. Otherwise, they are good, our brothers in suffering. The only thing is what are we going to do with this Jihad of theirs? It is something that is not at all good - it kills them more than us. It is difficult, but we must stay close, for even if we wanted, we could not run away from each other. The solution is to talk, and not to devour each other inhumanly. It is unsightly and disgraceful, and we cannot annihilate each other. God will not let it happen!” While reading this book on the contribution of generous Patriarch Pavle to the dialogue with Muslims, written by hard-working, worthy and enterprising Aleksandar Prascevic, I remembered a sunny October day, on which our Patriarch willingly accepted to perform a religious service on a raft with an improvised alter on it, although, as he had admitted he could not swim, and thus did not feel quite comfortable.

For the sake of Christian, Serbian and overall human good Patriarch Pavle was always ready as an apostle to “swim” in all waters, even in those most muddy and dirtiest, that emerged polluting and flooding our social reality and our souls, which could not touch him at all in His Holiness, let alone make sully him with their mud. It was mostly recognized by all, even by those who, among the Serbian enemies, but also among some Serbs with narrow awareness, love of truth and responsibility for the publically spoken word could not control their shameless defamations and the most outrageous lies about those with different opinions and opponents in ideological, political and armed conflicts. Although small in number, there were also those who monstrously accused the Serbian spiritual leader for various crimes and supposed spiritual leadership in the alleged criminal undertaking directed to destroy others and different members of the former Yugoslav brotherhood, and in particular to destroy the Muslims. Nevertheless, after the Patriarch had passed away (2009) and moved from here to eternity, the highest Muslim religious leaders expressed their deepest condolences, while Mufti Muamer Zukorlić, known for his often sharp, and even inappropriate and inflammable words on some occasions, wrote, inter alia, that the late Patriarch “was a man that had acknowledged consistency with his own spirituality and compliance of his acts, words and beliefs, which is very rare in the modern world”. One of the virtues of true saint-like living is the complete - to men as “weak beings” (V. Jerotić), hardly accomplishable accordance between beliefs, words and acts. This all characterized the monk and Patriarch Pavle to the largest extent. It is well known to the contemporaries of this “walking saint”, a pedestrian among other pedestrians on the earth, who repaired his own shoes and rose at the break of dawn, because, as he used to say “nights are the time to sleep and days are the time to work and pray”. However, time flies without stopping, and there are not many witnesses of the Patriarch’s impeccable energy. The anecdotes about his exceptionality gain a legendary gold coating, so that one may think an idealization was in process, habitual of story-telling which does not bypass human icons of all times and from all places, and thus at least partially deprives them of the characteristic of realistic authenticity. For this very reason it is necessary to explain and substantiate whatever is not and whatever cannot be disputable related to the Patriarch’s life using reliable facts and acts, which is, however, insufficiently known in details, and thus risks being relegated to the badly lit past, archive storage and the uncertainty of fragile human memory. At the same time, since Patriarch Pavle was the Head of the Serbian Orthodox Church in one of the most difficult periods of our recent history, when in addition to existential, there were no less dangerous shadows of propaganda campaigns and defamations from several directions, spread above it and above the entire Serbian population, it is of wider and far-reaching importance to remind with arguments of the manner in which he led and guided his Church, clergy and believers. To this very objective - the building of factual foundations for stable knowledge of our (unfinished) past, reasonable self-cognition and fair representation with others, and as an unavoidable starting point for various further studies, this second book by Aleksandar Prascevic will serve preciously, dedicated to the contribution of Patriarch Pavle to the relations of the Serbian Orthodox Church with our Muslims, and with Islam, in fact with the Muslim world in general, during the period from 1998 to 2009.

The decision to collect, prepare and publish the data on Patriarch Pavle’s contribution to the dialogue with Muslims, which also encompasses all activities of the Serbian Orthodox Church in this respect, proved to be timely and sound already on the occasion of the publication of Prascevic’s first book in the feuilletonist manner in Politika daily, under the title of Patriarch Pavle on Islam and Muslims (1990-1997). The book publication (2018) only confirmed the existence of great interests in this neglected area church activities and inter-religious communication. The special value of the data, analyses and assessments stated in the previous book result from the sensitive topics of a war-disturbed era, in which the relations between Orthodox Serbs and Muslims/Bosniaks were undergoing brutal historical, socio-psychological and moral trials, with permanent consequences and traumas, which are also visible at present. In general, it has been demonstrated that the thread of contact between the Serbian Orthodox Church and the Islamic Community was maintained, primarily in Belgrade and Serbia, although also at a wider level, even under the most difficult circumstances, when conventional, courtesy and formal forms of communication are of essential importance. To a great extent thanks to the personal efforts and example of Patriarch Pavle, who was not obligingly silent about the crimes committed on the side of the Muslims and always pointed out the same on the side of his own Church and people, warning them that above all and primarily we must be human - the very sensitive, often invisible, threads of the Orthodox-Muslim relations were preserved. This new book from Prascevic, which is by all means like the first one, a result of previous researches for his future postdoctoral paper in Thessaloniki, encompasses the post-war period up until the death of Patriarch Pavle. The same concept and methodology are also present in this second book in the form of a unique objective monograph, which is understandable and logical, in particular in view of the very convincing and successfully carried out procedure in the first book. Let us point out the documentary exhaustiveness of Prascevic’s book in the first place. Using the data from all available primary and secondary sources, from archives, through reference books and decisions of the church bodies and institutions, to periodical and individual publications and printed matter, as well as scarce existing author’s studies, this hard-working researcher diligently collected, classified and presented all the documents relevant for a comprehensive insight into Patriarch Pavle’s contribution to the dialogue or, rather, to existential contacts with the Muslims. At the same time, it is an exhaustive and comprehensive review of Orthodox-Muslim institutional contacts, in chronological order, enabling us to perceive an important and rather hidden dimension of social and religious interaction in Serbia, in the territory of the former Yugoslavia, and also within a wider scope of inter-religious dialogue, where the Serbian Orthodox Church had been incomparably present and more active than is usually assumed. Prascevic’s contribution to the information on this issue is of fundamental and essential value, because it establishes a firm reliable base, as a hitherto non-existent precondition for any further serious examination. In fact, he has drawn out into the light an entire neglected and hidden but important area of existence and communication of our Church with its surroundings and the world - from the discomfort of implication and uncertainty of self-examination, which has a certain dose of preventive and self-protective hypocrisy. Far from it that one should rush to embrace Islam and Muslims innaively and in a self-sacrificing manner just to eliminate often maliciously expressed criticism because of alleged reservedness and repulsion of our Church, because it would be meaningless and counter-productive, thus harmful as well, for both Orthodox Christianity and the prospects of establishment of a realistically feasible and desirable measure of reciprocity with Muslims, with whom we are destined to share the same living and social space. The measures Archbishop Anastasije had in mind and which Patriarch Pavle persistently believed in, and proved through by his acts until his last breath. Although to the casual eye Prascevic’s monograph may seem primarily, and almost explicitly of a documentary character, which in fact it is, it would mean that its epistemological and educational potential has not been recognized and evaluated to the end. Namely, the author has managed, with modesty and awareness to serve the theme about which he informs us in a factual and objective manner, and succeeded tentatively, to direct the reader’s attention non-obtrusively, in brief comments and notes, suggesting in a concise manner his own value judgement the facts he is referring to. The novelty and value of the two books by Aleksandar Prascevic will be revealed in full only when they start being cited in bibliographies of future researches, as unavoidable sources, which, we hope, will not take long. In any case, we are impatient to see new insights that this young but already experienced researcher is going to convey in his postdoctoral Thessaloniki study entitled Contribution of the Serbian Orthodox Church to Dialogue with Muslims. Prascevic has already contributed considerably to this dialogue.

Darko Tanasković, Ph.D.

Professor at the Faculty of Philology of the University of Belgrade