Historical Survey of Ancient Versions

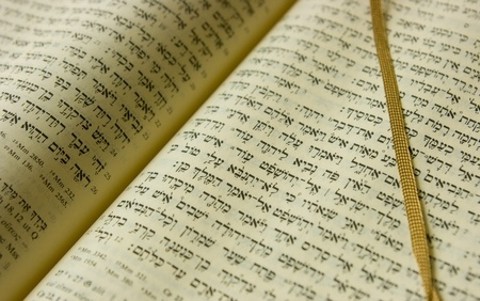

1. Earliest Versions of the Hebrew Bible.

1. Earliest Versions of the Hebrew Bible.

The deportation of the Jewish people to Mesopotamiadeprived them of their temple worship and they were thrown back upon scripture for a principle of coherence of religious and national identity. Thus the returning exiles in the following century, although they restored the worship of the temple, adhered to the Law and its public reading, as the books of Ezra

and Nehemiah reveal. Nor were the Jews now confined to Palestine: at the time of the deportation, there were already communities of exiles in Egypt, and the community there grew under Persian rule, while a Jewish population remained in Mesopotamia. The successors of Alexander the Great encouraged people of many races to settle in newly established cities, and Jews thus greatly increased in number in Egypt, and spread throughout the Hellenistic world. All these events brought linguistic change of habit. Aramaic, for Palestinian and Mesopotamian Jews, took the place of Hebrew as the vernacular, while the Jews of the Hellenistic cities adopted Greek as their tongue. These are the languages of the first translations of biblical writings, on the one hand the Targumim, on the other the Greek translation known as the Septuagint (LXX).

a. Aramaic. Tradition has the origin of the Aramaic translations or Targumim in the days of the return from exile, and Neh 8:8 is taken to refer to translation being given when the Hebrew scriptures are read,

in this case, the participle mĕpōrāš, is taken to mean ―with an interpretation‖ rather than simply clearly,‖or ―distinctly‖. However, the tradition cannot be substantiated. But it is clear from the Qumran scrolls, the NT, and passages of the Mishnah, that by the end of the Second Commonwealth, Targumic interpretations were part of the exegetical inheritance among the Jews. See also TARGUM, TARGUMIM. Such translations would at first have been transmitted in oral tradition, and only later committed to writing. In the earlier Targumim, there is a certain amount of haggadic material or MIDRASH introduced along with the Aramaic rendering of the Hebrew text: this illustrates how the two senses of ―interpretation‖ are present in this translation. Not only are obscure passages given a more specific application in this way, but edifying or merely interesting detail is added to the accounts. In the later Targumim, this element is not entirely absent but has been reduced. The discoveries in the materials from the Cairo Genizah, from Qumran, and in the Codex Neofiti of the Vatican library, have shown the variety of renderings which existed, sometimes showing links with the kind of textual variation in the Hebrew which the Qumran finds in particular have revealed. This suggests that in origin the translations represented may have arisen in different places or communities. (For a good survey, see Bowker 1969.).

b. Greek. It has been suggested by a few scholars that the Septuagint (LXX) translation arose in a similar way, with different Greek translations made in different Greek-speaking Jewish communities. In this way the different families of text within the LXX tradition are explained as the representatives of early forms of the texts, and not as later corruptions or revisions. See SEPTUAGINT. But although scholars of stature have put such views forward, they have not commanded general acceptance. The evidence is held by most experts to signify that, for the Pentateuch at least, we can accept the notion of a distinct single act of translation in the third century before the Christian era.

Such a specific dating is found in the Letter of Aristeas. This work purports to be a letter exchanged

between Greeks describing the origin of the Greek rendering of the Jewish Law. It is alleged to have been undertaken at the command of Ptolemy II Philadelpus (283–246 B.C.E.) at the instigation of his librarian Demetrius of Phalerum. At the request of the king, the Jewish high priest sends seventy-two scholars who finish the translation in as many days. (Later forms of the story in Christian writers introduce the miracle that these scholars worked in pairs without consultation with any others, and upon collation, were found to have produced the same identical Greek text!). The details of the story will not stand up to investigation. Demetrius was not Ptolemy‘s librarian, and was in fact banished by him. Moreover, the story, though purporting to be the work of a Greek, is written in many respects from a Jewish point of view. However, it is generally conceded that in spite of this, the origin of the translation should be placed at the date, apparently traditional, which the Letter ascribes to it. (For a survey of the LXX, see Jellicoe 1974.) See ARISTEAS, LETTER OF.

Examination of the text of the Greek OT shows that its translation was the work of a number of translators: we may date the rendering of the Pentateuch in the 3d century, and it would appear from the Prologue to Ecclesiasticus (ca. 116 B.C.E.) that by that date the whole of the Jewish scriptures had been rendered. This is also demonstrable from the use of the translation made by Alexandrian Jewish historians and a probable echo of the translation of Isaiah in the work of the poet and scholar Callimachus (ca. 300–240 B.C.E.). The style differs: much is marked by a tendency to imitate Hebrew constructions in the Greek, but there are varying degrees of such literalness. Some Wisdom books are marked on the other hand by great freedom, which sometimes strays far from the sense of the original: perhaps the great difficulty of parts of the original encouraged this.

In general, there was great concern for accuracy, and from this arose a succession of revisions of the text. Our earlier knowledge of this from later Christian scholars has been enhanced and rendered more precise by manuscript discoveries in the caves by the Dead Sea at Qumran and Muraba‘at. See DEAD SEA SCROLLS; WADI MURABBAAT. Certain manuscripts characterized particularly by the rendering of the Hebrew wĕgam by the Greek kaige have been associated with the name of Theodotion, previously assumed to have lived in the late 2d century of the Christian era, but now by the dating of the manuscripts necessarily placed at an earlier date, the first century B.C.E. or C.E. The name of Theodotion was already known, along with those of Aquila and Symmachus, as revisors of the Greek text, whose motivation was greater accuracy and verbal equivalence between the Hebrew original and the Greek rendering. See AQUILA‘S VERSION; SYMMACHUS, SYMMACHUS‘S VERSION; and THEODOTION, THEODOTION‘S VERSION.

References in early fathers and in marginal annotations provided our main source of knowledge until modern manuscript discovery filled out the picture. The context of their activity, especially that of Aquila, was theological controversy between Christian and Jew over the interpretation of the testimonies drawn from the Hebrew scriptures, which the Christian urged should be understood to support the claims made for Jesus Christ and the Church. In such controversy it became clear to the Christian participants that their arguments were rendered weak when based on passages where

the LXX differed from the Hebrew adduced by their Jewish opponents. As a reference aid in such

circumstances, the Alexandrian scholar Origen produced the six-columned work known as the

HEXAPLA. In this work, the Hebrew text, along with a transcription, was accompanied by the versions

of Theodotion, Aquila, and Symmachus (and by other versions in certain books), together with the text of the LXX, which Origen had provided with a critical apparatus to remedy its shortcomings. This work (of which a few manuscript traces have lately come to light), although intended to clarify, became at length a potential source of corruption as the significance of Origen‘s apparatus became incomprehensible. The work of the Antiochene Lucian also sought to provide a more accurate relationship between the Hebrew and the translated Greek text. See also GREEK VERSIONS below.

c. Syriac. In the opinion of many scholars, the Syriac Pentateuch is believed to have been a Jewish

translation in origin, although preserved in the Bible of the Syriac-speaking church. It has many contacts

with the Targumic tradition. It is suggested that the conversion of the royal house of Adiabene to Judaism in the 1st century C.E. was the occasion for this translation. A similar suggestion for the origin of the Latin version in Jewish circles in Antioch and its adaptation by the Christian church, made on mainly linguistic grounds, has not however met with acceptance. See SYRIAC VERSIONS below.

2. Earliest Versions of the Christian Bible.

The NT writings, in Greek, drew upon the text of the LXX and its variety: both Testaments were used by the church, after some time, as inspired scripture. The

church spread among Greek-speaking urban dwellers: here the inherited scriptures of the OT and NT were immediately available, and their influence is evident in early traces of the development of liturgy, canon law, theology, and the legends of the saints. But as the Gospel expanded in the course of the 2d century, it encountered and converted, both in the Latin speaking West and in the countryside of the Hellenized East, indigenous peoples unfamiliar with Greek. It must shortly have discovered the necessity of translating the scriptures which were the source of the substance and form of its belief and life. The translation of the OT for Jews who had lost Hebrew as a native tongue was the analogy of this; but, although there were many similarities in methods and in end-product, the analogy does not seem to have been recognized.

a. Latin and Syriac. The earliest translation appears to have been in Latin. See LATIN VERSIONS below. This appears in Africa towards the end of the 2d century: but it is not altogether certain that it originated there. An Eastern origin in Antioch and a N Italian origin in or near Milan have also been suggested. In textual terms, however, the form of the Latin version which survived in Africa appears to be the most primitive.

In the Syriac–speaking world of the East, a gospel tradition in the fourfold gospel form would appear to be attested fairly late, by comparison with the Latin: this is due to the creation in the 2d century C.E. of a

gospel harmony by the apologist TATIAN, a Syriac speaker by birth, who introduced his work, known

generally as the DIATESSARON, among his fellow Syriac speakers. The influence of this harmony upon the gospel text in Syriac was all-pervasive, even when a fourfold gospel form was adopted: it reveals itself in harmonistic readings and in other variants of theological Tendenz deriving from Tatian‘s encratite and anti-Judaic views. Such readings, through the influence of the Syriac text, have spread to versions derived from or influenced by it, such as the Armenian, Georgian, and Ethiopic (see Lyonnet and Vööbus).

Whether Tatian‘s harmony was composed in Greek (since he was in the West at the time of his

conversion and wrote in Greek before his return to his native Mesopotamia) is a question still debated. We have a 3d century fragment of the Diatessaron in Greek from the frontier town of Dura-Europos on the Euphrates, and it has recently been very plausibly argued that the Greek hymnodist Romanos the Melodist was influenced by the Diatesseron in the early 6th century. The above data, however, need not imply the existence of a Greek Diatessaron. Hence, the view once entertained by a number of scholars that such a document had influenced the text of such a witness as Codex Bezae is no longer canvassed.

There is still a stronger body of opinion that the Latin tradition was affected by the harmony of Tatian. This view rests not only upon the evidence of readings in the manuscripts of the Latin tradition, but also upon a number of gospel harmonies dated at various times throughout the Middle Ages in languages of Western Christendom (German, Dutch, English, Italian, and French). From this has been deduced the

existence of a Latin harmony, derived from Tatian‘s work, if not actually composed by him: and its corrupting influence upon the Latin text of the fourfold gospel has been suggested. But although several manuscripts of Latin harmonies are known, the view outlined is by no means that of all scholars, many of whom consider the Latin and Western harmony tradition to be an independent development, and its coincidences with what we know of Tatian‘s text to be fortuitous.

b. Coptic. The translation of the first Coptic version is not so precisely to be dated as that in Latin or

Syriac: however, the date cannot be later than the 3d century. The conversion of St. Antony through the

hearing of scripture about 270 C.E. indicated the existence of a Coptic version, since he knew no Greek,

and about 50 years later Pachomius, writing a rule for monks in Egypt, demanded the capacity to read

scripture, or to recite it, from postulants. The sensational find of NAG HAMMADI is of manuscripts of

the 4th century, among them the Gospel of Thomas, a collection of sayings attributed to Jesus, many of

them with parallels in the Synoptic Gospels. The translation of these in Coptic owes a great deal to the

canonical gospels in Coptic, and therefore presupposes their existence. All these data point to the 3d

century as the latest terminus a quo for the earliest Coptic translation. We have not only parts of the

gospels, but of many other parts of the Bible in the various dialects into which Coptic had developed by

the effect of the geography of the Nile Valley. The Sahidic dialect came to overwhelm the others in

course of time: this may be related to the fact that one of the others, sub-Achmimic, was preeminently the language of Gnosticism and Manichaeism, and the eventual triumph of orthodoxy brought the literary use of that dialect to an end. Sahidic in its turn was superseded by Bohairic, which remains the liturgical language of the Coptic church. The complicating factor of harmonization is not found in the Coptic gospels.

All other parts of the Bible, both NT and OT, were translated in due course. The different estimations of

the extent of the canon played their part in different areas. In the Syriac speaking regions, the NT lacks

the books of 2 Peter, 2 and 3 John, Jude, and Revelation, which were counted among the antilegomena in the early 4th century, according to Eusebius. The major part of the OT in Syriac, was rendered from

Hebrew, including the Wisdom of Jesus ben Sira (which only came to light in Hebrew within the last

hundred years): only the letter of Baruch, the additions to Daniel known only in Greek, and the deuterocanonical books of Tobit, Judith, the Wisdom of Solomon, and 1 Maccabees were rendered from Greek.

Latin and Coptic were rendered from Greek throughout the Bible, and the whole of the NT in Syriac.

3. Subsequent Versions and Editions. The three versions mentioned hitherto, Latin, Syriac, and

Coptic, are all termed ―primary versions‖ of the NT, since they are all rendered from the Greek text. For

the OT, in addition to the LXX, the only primary versions used by Christians were the Syriac and the

Latin Vulgate (most parts of which were translated from Hebrew by Jerome, but a few books were simply revised from the Old Latin, which was itself based on the LXX). See VULGATE. Later primary versions of the NT are attested for Gothic and Slavonic, each translated directly from Greek. See GOTHIC

VERSIONS below.

―Secondary versions‖ are those made from a translation, as opposed to the original language; thus, any version of the OT translated from the LXX is a secondary version. Syriac engendered many (the earliest stratum of the Armenian version, Arabic, Persian, and Sogdian), while the Ethiopic, translated from Greek, was subject to a revision from Syriac. Coptic also gave rise to Arabic translations and provided the base of the Apocalypse in Ethiopic. See ARMENIAN VERSIONS and ETHIOPIC

VERSIONS below.

As churches became established, and scholarship could arise, greater recourse to the original Hebrew or

Greek was made. Thus the Old Latin, in which there are different strands, was eventually revised, at least in part, by Jerome: the Old Syriac, with its debt to Tatian, was supplanted by the Peshitta. The Armenian turned to the LXX and the Greek NT for its revisions leading to later authorized versions. The Georgian version, in part at least the offspring of the Armenian, was revised to a Greek standard on more than one occasion. See GEORGIAN VERSIONS below. In Syriac, we have a valuable rendering of the critical work of Origen, the Hexapla, known therefore in Western scholarship as the SYRO-HEXAPLA version which seeks to give a word for word equivalence to the Greek. A similar NT version was also produced, known as the Harklean, after the birthplace of Thomas, its translator.

While the West was served in the earliest periods of Christian expansion by the Latin version alone, and

this continued to be the preeminent text of scripture throughout the Middle Ages, there were nevertheless translations into a number of languages of the Germanic invaders of the Roman Empire as these were converted, namely into Old High German, Anglo-Saxon or Old English, and Icelandic or Old Norse: while at a later period, translations and paraphrases are known in the Middle German, Middle English, Middle Dutch, Old French, and in the Tuscan and Venetian dialects of the medieval form of the Italian language.

The versions of the Bible entered into a new phase of influence with the invention of printing. In the

West, the Vulgate was committed to its first printed edition in the 15th century and became available for critical study as manuscripts were studied and compared. The various Eastern versions, which had begun to be known in the West through the attempts to unify the church in the 15th century, were the object of both Catholic and Protestant scholarship. Type for the major languages was already cut in the 16th century, but the appearance of full Bibles in some cases waited for more than a century. Where biblical texts were available, they found a place in the Polyglot Bibles of the 17th century. When editions with critical apparatus began to be made, beginning with Mill‘s in the early 18th century, the versions were included as fully as they were known (often, though, in case of the Eastern versions, in reliance upon Latin renderings, not always accurate). In the course of the 19th century, as textual criticism developed for the Hebrew Bible, the LXX and the NT, the evidence of the various versions (Latin, Greek, and Eastern) played an increasing part. Although opinions differ sharply on the weight to be given to evidence from these sources, they continue to occupy the attention even of those who underrate their importance. See TEXTUAL CRITICISM.

As to editions, the present position is far from perfect. For some versions, especially the Vulgate, we are

in a position of advantage, while for others there are projects of critical edition under way (e.g., the Old

Latin or the Peshitta OT). Others still, such as Coptic and Georgian, while having valuable editions of

many manuscripts available, still lack a critically coordinated edition. Others again, such as the Armenian

and the Ethiopic, are still not available in a critically useful form. The minor versions, both Oriental and

Western, are often very difficult of access. Another problem is that of manpower: while there may be

many scholars competent in a language important for Christian or Jewish antiquity, few may make

editorial or philological work on biblical (or indeed other relevant) texts their main research. For

languages which few Westerners still learn (Georgian, Sogdian, Nubian, medieval Western languages),

the situation is even more unsatisfactory to the biblical scholar (the cultural policy of the former Soviet

Republic of Georgia has made Georgian a special case). It should also be noted that the study of Latin

now is far less common or advanced than a generation or two ago.

B. The Critical Study of Ancient Versions

Before outlining the importance of the versions in a study of the Bible, a sketch must be given of the

necessary memoranda for users of versions for that or any other study. Every version has its own history, as the sketch above will have shown. This perhaps obvious fact has a number of ramifications. There may have been independent tentatives at translation when this was first undertaken, or a first attempt may have been neglected as a possible base of revision, at a later date, and a new translation begun. In establishing this, attention must be given to the way in which the same original is rendered in the language receiving the translation: the same text may be rendered in distinct ways. To trace this, we need access not only to manuscripts of the Bible, but to quotations from the Bible in the writers of the receiving language, and to liturgy, hymnody, and so on, in which scriptural words may have been adapted or echoed. The study of the Old Armenian by Lyonnet, and many classics of the study of the Old Latin version are fine examples of this type of research. A further corollary of this is that a manuscript does not necessarily represent the same version in all parts (as is true also, textually, of Greek manuscripts of the NT). Manuscripts and quotations, too, may also be the result of revision, which has produced a mixed text. This is a singularly difficult problem to deal with.

Whether studying the version itself, or in relation to its putative model, we must note its style and the

approach of the translator to his task. Does he paraphrase or gloss his model, or does he painstakingly, or even pedantically, reproduce his model word for word? Does he comprehend his text, or does he struggle? Does his translation derive from an original in which there were corruptions, such as mistakes in copying? Investigation of these aspects will be an aid to determining whether the version primarily comes from the original Greek or Hebrew, or whether it is a secondary or even tertiary version. In all this, we shall become aware of the limitations which the idiom of the receiving language has placed upon translation. For example, quoting a classic article by Ll. J. M. Bebb (1902), ―there are no distinctions of gender in

Armenian, no neuter in Arabic, no passive voice in Bohairic, no article in Latin, and therefore these

versions afford no help where readings involving such points are being discussed.‖

1. History of the Canon. The ancient versions are valuable objects of study, both in themselves and in

the context of the study of the Bible and of church history. First, they illuminate the history of the

development of the canon of scripture. The fact that the Samaritans possessed only the Pentateuch reflects the state of the concept of the extent of scripture at the time of the Samaritan schism. The Syriac NT canon, with the absence of the lesser Catholic Epistles and Revelation, corresponds to the contrast of homologoumena and antilegomena in Eusebius‘s description of canonical status in his day: the late rendering of Revelation into Georgian shows how long doubts about that book persisted within Eastern Christianity. On the other hand, the presence of the book of Enoch within the canon of the Ethiopic church illustrates that the existence of a penumbra to the canon could eventuate in inclusions as well as exclusions. It is often on the borders of Christendom that older states of the biblical literature survived,when the progress of theology and scholarship in the Greek ―center‖ had produced new parameters.

2. History of the Text. This also reveals itself in the second of the fields upon which the versions,

critically studied, may cast light, namely, the history of the text of scripture. We may use the versions, if

we know their history, to erect an historical framework for the dating of variant forms by a series of

termini ante quem. Often in dealing with the earliest variants and the earliest versions, it is the knowledge of the version‘s history that is the most difficult requirement to attain. As has been pointed out above (with respect to the translations into Syriac, Latin, and Coptic), we can only arrive at tentative and approximate conclusions about the place and date of the translations, and the same is true certainly of Georgian and Ethiopic, to mention only two other striking cases. We must beware of the circular

argument which is always there to entrap us. Nevertheless, we can argue, even in these important areas of problematic, that a reading existed ―by such and such a date, at least.‖ It has often been further deduced that such a reading existed in the original. Evidence coming to light in new discoveries sometimes confirms this, as when readings previously known only in Greek form, for instance, have been found in the Hebrew of Qumran documents. Can we make it a general rule however?

The study of the text of the NT continues to be bedeviled by debate over this point. In earlier days, when

the Greek evidence was largely confined to manuscripts dating from the 4th century C.E., a scholar such

as F. C. Burkitt could argue that the sharing of a reading by the oldest form of the Latin gospels and the

oldest form of the separated gospels in Syriac not only indicated its antiquity, but also guaranteed its

candidacy for consideration as the original text. Recently, in the work of Kurt and Barbara Aland in their

survey of the text of the NT (1987), and in many papers of Kurt Aland, we find such a view dismissed

with virulent scorn on the grounds that no such text as those versions presuppose had been found in the 2d and 3d century Greek papyri of the gospels we now possess. The methodological question involved here is found in the fact that the gospel manuscripts which the Alands can draw upon are of Egyptian origin, for it is only (with rare exception) in the climate of Egypt that papyrus survives to our day. Greek fathers, of other provenance but early date, such as Justin, Irenaeus, and Clement, can frequently be found to attest variants known otherwise only in the earliest versions, while the papyri do not invariably fail to share versional readings against other witnesses. Thus, the arguments of the Alands, while they justifiably draw attention to certain dangers of overemphasis in older use of the versions, themselves overemphasize their point. In spite of their misgivings, it cannot be gainsaid that in the versions we may find forms of text, or individual readings, which have left no traces in Greek manuscripts presently known to us. But in many cases the presence of such textual forms or readings in the quotations and allusions of early Greek Christian writers demonstrates that the readings of the versions were most probably derived from Greek manuscripts at the time of their translation.

3. The “Original Text.” This leads to the third aspect of biblical study upon which the versions have

been held to have a bearing, namely, the establishment of the original text. The use to which versional

evidence has been put has differed in the NT and the OT. In the NT the method has usually been as in the case outlined. The coincidence in reading between versions either against the Greek tradition as a whole, or supporting one or a few significant witnesses against the rest of the Greek tradition, has been held to give a reading acceptable as original. But this has not generally been applied in any mechanical way, but the argument for any acceptable reading has been reinforced by the arguments of rational criticism.

In the OT, versional evidence has generally been that derived from the LXX: readings in which the

meaning of the Greek differed materially from the Masoretic text of the Hebrew have at certain periods

been made the basis of conjectural emendation of the Hebrew text, based either upon paleographical

considerations or upon comparative philological considerations which have drawn upon real or alleged

alternative meanings of the same roots, which would explain the LXX rendering. Such approaches have

aroused dissent, and trenchant criticisms have been made; nevertheless, the renderings of the New English Bible in its OT portion bear the marks of this type of textual procedure. However, in some cases, the finds of Qumran have revealed the existence of Hebrew originals upon which the Septuagintal renderings have been based. This removes the debate from the field of the versional evidence to that of a critical choice between variations now known to have existed in different text-types of the original.

Variant readings in the original or in versions, apart from those which may arise from sheer error, may

be due to the understanding of the text. This may come either from the knowledge of the language from

which the translation is made by the translator, or from a tradition of exegesis which he has inherited.

Thus, the versions are of value in both these ways. They reveal to us the understanding of obscure words or the resolution of ambiguous punctuation as those were circulating in Christian circles, and they may also show the exegesis current at the time of translation. Exegetical translation often comes about by making the generalized more specific or by clarificatory additions. There are many examples in the

Targumim, especially in passages such as Genesis 49 and Isaiah 53. Lexicographical material latent in

translations is most readily seen in the NT, since the earliest translations in that case are only a few

centuries later than the original, when much the same Greek was still spoken.

4. The Ancient Languages Themselves. The last matter upon which the ancient versions bear takes us

outside biblical study itself, namely the history of the languages of the versions. It is often the case that

the Bible version is the earliest source for our knowledge of the language, or that it constitutes a valuable corpus of information about the language dateable to a particular time. So, for example, Gothic, Armenian, and Georgian biblical versions are a primary source for our study of the languages in which they are composed, while the Greek of the LXX, the Latin of the Bible, and the dialects of Coptic known from biblical versions are important corpora representing well defined stages in the history of those languages.

The ancient versions, insofar as they represent pioneering work in the activity of translation, also

provide a significant chapter in that aspect of intellectual history. Detailed work upon the methods of the translators and the pitfalls which beset them will illuminate questions which have only recently attracted full investigation as modern linguistic science has expanded. The ancient translators, for the most part unknown by name, have not left much theoretical discussion of their endeavor. There are, however, interesting remarks to be found in several works of Jerome (see e.g., Kelly 1975, chap 15).

Both in its specifically biblical application and in its more general ramifications, the study of the ancient

versions is a field still containing much that is worth discovery, examination, and discussion, bearing

upon biblical study, church history, the history of doctrine, and linguistic study of many kinds. It is to be

encouraged and presented as an area deserving the attention of both seasoned scholars and beginners.

(Surveys of the subject may be found in the articles ―Bibelhandschriften‖ and ―Bibeluebersetzungen‖

from TRE 6, Lieferung 1/2 [1976].)

Bibliography

Aland, K. 1972. Die alten Uebersetzungen des NeuenTestaments, die Kirchenvaeter und Lektionare. ANTF 5. Berlin and New York.

Aland, K., and Aland B. 1987. The Text of the New Testament. Trans. E. F. Rhodes. Grand Rapids.

Assfalg, J., and Krueger, P. 1975. Kleines Wörterbuch des Christlichen Orients. Wiesbaden.

Barr, J. 1968. Comparative Philology and the Text of the Old Testament. Oxford.

Bebb, Ll. J. M. 1902. Versions. HDB 4: 848–855.

Bowker, J. 1969. The Targums and Rabbinic Literature. Cambridge.

Burkitt, F. C. 1903. Text and Versions. EncBib 4: 4977–5031.

Eissfeldt, O. 1966. The Old Testament. An Introduction. Trans. Peter Ackroyd. Oxford.

Jellicoe, S. ed. 1974. Studies in the Septuagint: Origins, Recensions, and Interpretations. New York.

Kelly, J.N.D. 1975. Jerome. His Life, Writings, and Controversy. New York.

Kilpatrick, G. D. 1955. The Gentile Mission in Mark and Mark 13:9–11. Pp. 145–158 in Studies in the Gospels, ed. D. E. Nineham. Oxford.

Lyonnet, S. 1950. Les origines de la version armenienne et le Diatessaron. BibOr 13.

Metzger, B. M. 1962. Versions, Ancient. IDB 4: 749–760.

———. 1977. The Early Versions of the New Testament. Oxford.

Vööbus, A. 1954. Early Versions of the New Testament. Papers of the Estonian Theological Society in Exile 6. Stockholm.

J. NEVILLE BIRDSALL