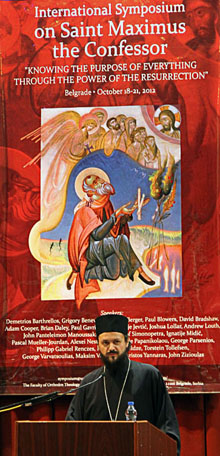

International Scientific Theological Symposium of Saint Maximus the Confessor in Belgrade

“Knowing the Purpose of Everything Through the Power of the Resurrection”:

The First Two Days

The St. Maximus the Confessor Symposium, “Knowing the Purpose of Everything Through the Power of the Resurrection,” co-hosted in Belgrade by the Belgrade Theological Faculty and the Orthodox Christian Studies Program of Fordham University, has begun with opening remarks by Bishop Maxim of Alhambra and the Western American Diocese, Patristics Professor at the Faculty and a Maximus scholar in his own right. Bishop Maxim introduced the new dean of the Faculty, Professor Predrag Puzović , who expressed his satisfaction at beginning his term as dean with such a grand event. He observed that St. Maximus is the “most universal spirit of his time and probably greatest thinker in the history of the Church. He has become the focal point of reference in modern Orthodox and Catholic dialogue.” The first church dedicated to St. Maximus, he noted, is in Serbia.

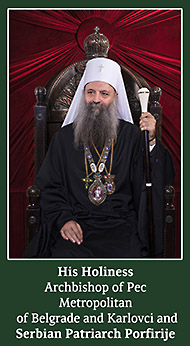

Bishop Maxim, chief organizer of the event, included in his welcome address, greetings to panelists and guests from His Holiness Bartholomew, Ecumenical Patriarch and His Holiness Irinej, Serbian Orthodox Patriarch.

Bishop Maxim, chief organizer of the event, included in his welcome address, greetings to panelists and guests from His Holiness Bartholomew, Ecumenical Patriarch and His Holiness Irinej, Serbian Orthodox Patriarch.

Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew, in his address, noted that “The Saints represent God’s gift to the world, precious beacons within the darkness of this transient world, and an example to be followed leading us to our final goal – the Kingdom of God.” Among these saints, who we commemorate this weekend, is the Confessor Maximus. Born in the sixth century and reposed in the seventh century, he, like all saints, belongs to the timelessness of the Kingdom of God, wherein we have him as a Heavenly intercessor before the Throne of Christ. The Ecumenical Patriarch highlight St. Maximus’s major contributions to theology in his address: his emphasis on love as the foremost of the virtues, his staunch defense of the two wills of Christ during the monothelite controversy, his distinction between the natural and the gnomic will, and his insistence that there is no natural evil, but the negligence of thoughts, from which stems mistaken actions and, important for a consideration of the contemporary ecological problem, the mistaken use of things that results from mistaken thoughts.

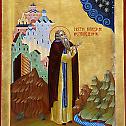

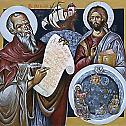

His Holiness Patriarch Irinej greeted the presenters and guests with an import note that by commemorating the 1350th anniversary of St. Maximus’s repose with this solemn symposium, we invoke his blessing. And truly his blessing has been invoked. Three monks from the Holy Monastery of St. Paul’s on Mt. Athos arrived on the opening day of the Symposium with the incorrupt hand of the Confessor, a generous donation to the Symposium from the Igumen Partheny. The Metropolitan of Pergamon, John Zizioulas, one of the speakers over the four-day event, served for the unveiling of the relic in the Faculty chapel. The grace was evident as the Maximus’s life in Christ, permeated with the Divine energies of God, manifest through his relics to fill the chapel with vivifying Heavenly grace. Hundreds of pilgrims bowed down in veneration before the Paschal mystery evident in St. Maximus.

Certainly, it is the power of the Resurrection manifest in his relics and holy prayers that make St. Maximus important not only for his theology but his witness to holiness. Over 40 artists captured the image of this holiness, which is the Divine image manifest in man, in a special art exhibit put together by Adrijana Krstić and Dragana Mašić to honor the subject of the Symposium. The art exhibit was also unveiled on the first night of the Symposium. Adorning the hallway that runs between the chapel and lecture hall, the artistry is a worthy tribute that connects St. Maximus’s spiritual and intellectual gifts to humanity.

Indeed the spiritual and the intellectual are tied together by the thread of St. Maximus’s witness to Christ, celebrated in this capital of the Balkans perched on a promontory above the rivers Sava and Danube. The Danube threads across Central Europe, leaving behind Proustian landscapes of cultural artifacts as it enters the Balkan Peninsula, where self-preservation coexists with transcendence. St. Maximus is a similar thread to link West and East. Here, in Belgrade, one encounters a parallel intellectual perspective threading remnants of German idealism with the lasting potency of the Byzantine legacy, which is most clearly articulated in the Logos-centered reality of St. Maximus the Confessor.

The talks of the first evening were available to all and featured the important issue of the context in which St. Maximus is received. The first to speak was Maximos, a monk from Simonopetra Monastery on Mt. Athos who is presently a theology professor at Holy Cross School of Theology in Boston. Fr. Maximos spoke on “The Relevance of His Thought Today,” in particular focusing on two of what he identified as three historical appropriations of the thought and writings of the Confessor: the Maximus translations of Anastasius Bibliothecarius (ca. 800-879) and John Eriugena (ca. 815-877), whose work was closely intertwined with the cultural politics of Rome and the Carolingian court of Charles the Bald, and Maximus’s popularity in the 11th century Byzantine court. Both of these appropriations illustrate different sociologies of translation that reveal how contemporary preoccupations inform our reception of Maximus. At issue are the passions of the day that, until rooted out, result in the fragmentation that is indemic to our society. This fragmentation is rooted in a spirtiual pathology for which Maximus offers a cure, if only we avail ourselves of his entire teaching and not what we think is relevant.

The 2012 winner of the Ratzinger Prize, “The Nobel Prize for Theology,” Fr. Brian Daley, followed with a consideration of “Maximus the Confessor, Leontius of Byzantium, and the late Aristotelian Metaphysics of the Person.” Fr. Daley is a well known historical theologian specializing in the early Church. He continued his studies of the fifth through eighth centuries on this evening, where he delved into Maximus’s Christology, which culminates with Maximus’s realization that Christ must himself be free as both creator and creature in one acting, free subject. By being two, a number that had heretofore signified division in God, the infinite becomes finite with so great a love for the world that He is able to save it. This is a Christology that is soteriological and that ventures beyond the traditional boundaries of metaphysics. There was a question and answer period, which Bishop Maxim said provided a “robust beginning to the conference.”

As the host for the Symposium, the Belgrade Theological Faculty is also able to enrich the Symposium with its liturgical schedule.

Friday began with Orthros and Divine Liturgy, served by Bishop David of Kruševac. The first session of the morning was chaired by Bishop Porfirije of the Faculty and featured Fr. Joshua Lollar from the University of Kansas, Professor Aristotle Papanikolaou of Fordham University’s Orthodox Christian Studies Program, and Adam Cooper from the Pontifical John Paul II Institute on Marriage and Family. All of the Symposium proceedings can be viewed online for 15 €, which defrays the cost of setting up remote live access to the Symposium, here: http://streaming.ni.ac.rs/a58ef6e274c

Fr. Joshua began the day with a consideration of “Pathos and Technê in St. Maximus the Confessor,” which generated considerable interest in the question and answer period. His paper brought Maximus the Confessor’s notion of pathos, which is the beginning of philosophy for Maximus, into contact with the contemporary and urgent question of technology and human life in the twenty-first century. Using Ambigua 6–8 and Ambiguum 45 to illustrate these concepts in relation to the state of human passivity in relation to the development of human technology for coping with an environment that afflicts that passivity, Lollar takes Maximus’s understanding that pathos resides at the heart of human nature, and asks whether technological attempts to overcome human passibility constitute an altering of human nature itself.

Professor Papanikolaou followed with “Learning How to Love: St. Maximus on Virtue,” which unflinchingly brought contemporary issues of soldiers dealing with Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) into dialogue with Maximus’s teaching on the virtues, in particular, love, the chief virtue. According to St. Maximus, the human is created to learn how to love, and is in constant battle against that which weakens the capacity to love. Virtues are necessary for the learning and acquisition of love: “All the virtues assist the mind in the pursuit of divine love” (1.11). Papanikolaou emphasizes St. Maximus’s complicated detailing of the relation of virtues and vices to the inner life of the human person and to human agency as a “progress in the love of God,” (2.14), which is measured ultimately by how one relates to others, especially those to whom one feels hatred or anger.

Concluding the morning panel was Adam Cooper, whose “St. Maximus on the Mystery of Marriage & the Body: A Reconsideration,” Bishop Porfirije correctly noted, demonstrates that “Christianity shows great emphasis on the body.” Cooper seeked to contextualize an analysis of a few texts within the tradition of Christian thought and within Cooper’s own formation and development, and within the Institute of John Paul II of Marriage (founded 1981), and the context of the confused and hyper-sexualized society of the West, especially using Centuries on Love 230 and 233.

During the question and answer period, Bishop Atansije (Jevtic), who himself speaks on Saturday, after complimenting Lollar, noted, “In Maximus’s thought, his estimation of pathos, “We are under the pathos, which is neither positive nor negative, the human being as created is a gift from God, it is not negative, it is rather, a capacity of participating in communion & love, which is a sort of pathos. God’s providence and Wisdom is called techniqes, it is in the realm of art.” Such is the caliber of this Symposium that the world’s foremost theologians are in the audience participating in an ongoing conversation with their peers on stage.

A second session chaired by Prof. Papanikolaou immediately followed. First to speak was Fr. Demetrios Barthrelos on “St. Maximus’s Contributions to the Notion of Freedom.” Barthrelos recounted that central to this notion of freedom is Maximus’s treatment of the will, which includes both the rational and the subrational. Human will is primarily understood by Maximus as self-determination. It is a natural faculty, but its actualization in concrete acts of willing depends on the person. Barthrelos argued that Maximus described the will in its fallen state as dominated by ignorance and deliberation, but also as continuously oscillating between choices that may be God-pleasing or sinful. In its perfected state, as it appears in Christ, it is steadily and unhesitatingly oriented to the doing of the will of God. He concluded by arguing that this does not threaten the integrity and authenticity of human freedom, but is rather its fullest and highest form.

This talk was followed by that of the chair of the Department of Philosophy at the University of Kentucky, Professor David Bradshaw. A specialist in the history of philosophy, Bradshaw delved into the history of the will by asking when the concept of the will originated. He said that most scholars point to Stoicism or Augustine, but that the will is already present in Plato. Maximus’s contribution to the will was formulated in his a response to monothelitism, which was a result of monoenergism, where it is clear that Maximus is interested in the form natural will takes in rational beings. His famous distinction between the natural and gnomic will is predicated on the gnomic (an act of choice) will not being a faculty (which the natural will is), but an act made possible by the natural will.

The panel concluded with Professor Torstein Tollefsen, philosophy professor at the University of Oslo, considering “Essence, Potentiality, and Activity in Maximus’s Conception of Hypostasis.” It is Maximus’s understanding of essence that provides the basis for Tollefsen’s claim about Maximus’s idea of self-understanding, which revolves around Maximus’s use of ousia, dynamis, and energia.

The Symposium continued in convivial fashion over lunch before returning to a session that delved deep into Maximus’s notion of the gnomic will. George Varvatsoulias presented on “Ruminative Thinking & Psychopathology Issues in the Writings of St. Maximus the Confessor: An Evolutionary Psychological Perspective.” Ruminative thinking is a reasoning process where individuals dwell on the same thought or theme for long time; it is characterized by focusing too much on negative appraisals about oneself. In terms of evolutionary psychology, it explains our ancestors’ need to protect themselves from potential threats by adapting to and fulfilling their survival needs. Ruminative thinking literally means believing that what took place in the past, will again repeat itself. In St. Maximus’s writings, rumination can be found under the concept of μηρυκισμὸς, which is not a regular term. This term is rarely found in his writings for he uses connotations to describe it, such as περιποιήσασθαι, συντηρῆσθαι, ἐπιφερομένων, τυποῦσθαι, when he talks of the conditions of the soul in terms of the maladaptive habit of the intellect towards impassioned thoughts. Tollefsen employs two existing questionnaires, 1) The “Responses Styles Questionnaire” (1987) and 2) A self-devised questionnaire composed out of St. Maximus references to ruminative thinking in order to test the hypothesis that the more individuals ruminate the more effectively psychopathological issues can be dealt with.

Fr. John Panteleimon Manoussakis, of Holy Cross (Boston), gave a recently written paper that specifically addressed a controversy in Greece right now concerning the gnomic will: “The Elected Will in St. Maximus,” which is based on a dialectical relation between nature and self. However, Manoussakis avoided reductive over categorization by recalling that the person is always more than its nature. Only persons can be partakers of the communion with God that began with the world’s creation and will end in the great eschaton.

Fr. Philipp Gabriel Renezes, in “The Concept of ‘Habitus in Theological Anthropology of St. Maximus” insisted that there is no gnomic will in Christ even if there is an apparent change in Christ’s human will. Renezes reaches this conclusion by way of his study of hexis, a problematic and unsatisfying term that expresses one of the connections between human nature and the divine. Perhaps best considered what we might otherwise call “virtue,” helps us understand Maximus’s notion of divinization, which is the encounter of the human person with the transforming and liberating freedom of God.

After dinner, a final panel for Friday the 19th consisted of Paul Blowers’s “The Interpretive Dance: Concealment, Disclosure, and Deferral of Meaning in Maximus the Confessor’s Hermeneutical Theology” and Nino Sakvarelidze’s “How to Read and Understand Patristic Texts Today? Contextualization and Actualization of St. Maximus’ Textual and Spiritual Heritage.”

Blowers, a professor church history at Emmanuel Christian Seminary, argued for the transformative possibilities through divine revelation. It is a divine revelation manifest through the Logos, manifest through what Blowers calls the “interpretive dance” of Maximus hermeneutics. In the tradition of Origen and Gregory of Nyssa, and with aid from the Areopagite’s notion of the divine “ecstatic” movement, Blowers argues that Maximus understands exegesis in some sense as an erotic interpretive “dance” in which the interpreter is being ecstatically drawn out of his or her intellectual and spiritual constraints into the deifying presence of the elusive Christ, who alone satisfies all desires.

Sakvarelidze’s historical-critical essay deals with Maximus’s reception in Georgia and it is a keen study of terms in order to build to the hypothesis that she tests. The paper focuses on two central questions: the contextualization of St. Maximus’s traditional-synthetic and innovative-systematic thought within Old Georgian and the translation and transportation of St. Maximus’ texts and thinking into the Georgian geographical, linguistic and cultural context.

Speaking of contexts, as we mentioned, Maximus is the thread tying together the intellectual and the spiritual, the cultural and the noetic. How could this be better expressed then marking the mid-way point of the Symposium on St. Maximus with an All-night Vigil and Divine Liturgy for the Confessor in the presence of his relics. Bishop David served the Vigil and Bishop Maxim served the Hierarchical Divine Liturgy with Bishop David and seven other priests concelebrating. Beginning at 8 pm, the Liturgy did not conclude until a quarter past one in the morning, although to mark such messianic moments of aeonic time with a chronometer is to distort the truth behind this synaxis of the sanctified Confessor and the struggling Faithful: this was Eternity in a continuous anamnetic reflection of the “Resurrectional present” and it was experienced by hundreds of the faithful who came together to celebrate the Eucharistic joy of our Lord and to taste what St. Maximus knows: the power of the Resurrection.