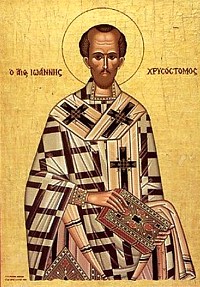

The legion of saints of the Church is comprised of men of extraordinary ability whose talents may have been dissimilar but many of whom seem to have shared a common genius for oratory. Yet out of this vast assembly of eloquent speakers, whose reputation might have rested on their gift of expression alone, the one for whom the title "Chrysostom" (in Russian, "Zlatoust"), or "golden-mouthed" was reserved, was John of Antioch, known as St. John Chrysostom, a great distinction in view of the qualifications of so many others.

Endeared as one of the four great doctors of the Church, St. John Chrysostom was born in 347 in Antioch, Syria and was prepared for a career in law under the renowned Libanius, who marveled at his pupil's eloquence and foresaw a brilliant career for his pupil as statesman and lawgiver. But John decided, after he had been baptised at the age of 23, to abandon the law in favour of service to the Saviour. He entered a monastery which served to educate him in preparation for his ordination as a priest in 386 AD. From the pulpit there emerged John, a preacher whose oratorical excellence gained him a reputation throughout the Christian world, a recognition which spurred him to even greater expression that found favour with everyone but the Empress Eudoxia, whom he saw fit to examine in some of his sermons.

When St. John was forty-nine years old, his immense popularity earned him election to the Patriarchate of Constantinople, a prestigious post from which he launched a crusade against excessiveness and extreme wealth which the Empress construed as a personal affront to her and her royal court. This also gave rise to sinister forces that envied his tremendous influence. His enemies found an instrument for his indictment when they discovered that he had harboured some pious monks who had been excommunicated by his archrival Theophilos, Bishop of Alexandria, who falsely accused John of treason and surreptitiously plotted his exile.

When it was discovered that the great St. John had been exiled by the puppets of the state, there arose such a clamour of protest, promising a real threat of civil disobedience, that not even the royal court dared to confront the angry multitudes and St John was restored to his post. At about this time he put a stop to a practice which was offensive to him, although none of his predecessors outwardly considered it disrespectful; this practice was applauding in church, which would be considered extremely vulgar today, and the absence of which has added to the solemnity of Church services.

St. John delivered a sermon in which he deplored the adulation of a frenzied crowd at the unveiling of a public statue of the Empress Eudoxia. His sermon was grossly exaggerated by his enemies, and by the time it reached the ears of the Empress it resulted in his permanent exile from his beloved city of Constantinople. The humiliation of banishment did not deter the gallant, golden-mouthed St. John, who continued to communicate with the Church and wrote his precious prose until he died in the lonely reaches of Pontus in 407.

The treasure of treatises and letters which St. John left behind, included the moving sermon that is heard at Easter Sunday services. The loss of his sermons which were not set down on paper is incalculable. Nevertheless, the immense store of his excellent literature reveals his insight, straightforwardness, and rhetorical splendour, and commands a position of the greatest respect and influence in Christian thought, rivaling that of other Fathers of the Church. His liturgy, which we respectfully chant on Sundays, is a living testimony of his greatness.

The slight, five-foot St. John stood tall in his defiance of state authority, bowing only to God and never yielding the high principles of Christianity to expediency or personal welfare. In the words of his pupil, Cassia of Marseilles, "It would be a great thing to attain his stature, but it would be difficult. Nevertheless, a following of him is lovely and magnificent."

It is impossible to cover the entire life of St John Chrysostom in a few pages. However apart from providing a very brief outline of his life, we have included a little more information about his life as a monk and as Patriarch of Constantinople.

Chrysostom as a Monk (AD 374-381)

After the death of his mother, Chrysostom fled from the seductions and tumults of city life to the monastic solitude of the mountains south of Antioch, and there spent six happy years in theological study and sacred meditation and prayer. Monasticism was to him (as to many other great teachers of the Church) a profitable school of spiritual experience and self-government. He embraced this mode of life as "the true philosophy" from the purest motives, and brought into it intellect and cultivation enough to make the seclusion available for moral and spiritual growth.

He gives us a lively description of the bright side of this monastic life. The monks lived in separate cells or huts, but according to a common rule and under the authority of an abbot. They wore coarse garments of camel's hair or goat's hair over their linen tunics. They rose before sunrise, and began the day by singing a hymn of praise and common prayer under the leadership of the abbot. Then they went to their allotted task, some to read, others to write, others to manual labour for the support of the poor. Four hours in each day were devoted to prayer and singing. Their only food was bread and water, except in case of sickness. They slept on straw couches, free from care and anxiety. There was no need of bolts and bars. They held all things in common, and the words of "mine and thine," which cause innumerable strifes in the world, were unknown among the brethren. If one died, he caused no lamentation, but thanksgiving, and was carried to the grave amidst hymns of praise; for he was not dead, but "perfected," and permitted to behold the face of Christ. For them to live was Christ, and to die was gain.

Chrysostom was an admirer of active and useful monasticism, and warns against the dangers of idle contemplation. He shows that the words of our Lord, "One thing is needful"; "Take no anxious thought for the morrow"; "Labour not for the meat that perisheth," do not inculcate total abstinence from work, but only undue anxiety about worldly things, and must be harmonised with the apostolic exhortation to labour and to do good. He defends monastic seclusion on account of the prevailing immorality in the cities, which made it almost impossible to cultivate there a higher Christian life.

Chrysostom as Patriarch of Constantinople (AD 398-404)

After the death of Nectarius towards the end of the year 397, Chrysostom was chosen, entirely without his own agency and even against his remonstrance, archbishop of Constantinople. He was hurried away from Antioch by a military escort, to avoid a commotion in the congregation and to make resistance useless. He was consecrated Feb. 26, 398, by his Theophilus, patriarch of Alexandria, who reluctantly yielded to the command of the Emperor Arcadius.

Constantinople, built by Constantine the Great in 330, on the site of Byzantium, assumed as the Eastern capital of the Roman empire the first position among the Episcopal sees of the East, and became the centre of court theology, court intrigues, and theological controversies.

Chrysostom soon gained by his eloquent sermons the admiration of the people, of the weak Emperor Arcadius, and, at first, even of his wife Eudoxia, with whom he afterwards waged a deadly war. He extended his pastoral care to the Goths who were becoming numerous in Constantinople, had a part of the Bible translated for them, often preached to them himself through an interpreter, and sent missionaries to the Gothic and Scythian tribes on the Danube. He continued to direct by correspondence those missionary operations even during his exile. For a short time he enjoyed the height of power and popularity.

But he also made enemies by his denunciations of the vices and follies of the clergy and aristocracy. He emptied the Episcopal palace of its costly plate and furniture and sold it for the benefit of the poor and the hospitals. He introduced his strict ascetic habits and reduced the luxurious household of his predecessors to the strictest simplicity. He devoted his large income to benevolence. He refused invitations to banquets, gave no dinner parties, and ate the simplest fare in his solitary chamber. He denounced unsparingly luxurious habits in eating and dressing, and enjoined upon the rich the duty of almsgiving to an extent that tended to increase rather than diminish the number of beggars who swarmed in the streets and around the churches and public baths. He disciplined the vicious clergy and opposed the perilous and immoral habit of unmarried priests of living under the same roof with "spiritual sisters." This habit dated from an earlier age, and was a reaction against celibacy. Cyprian had raised his protest against it, and the Council of Nicea forbade unmarried priests to live with any females except close relations.

Chrysostom's unpopularity was increased by his irritability and obstinacy. The Empress Eudoxia was jealous of his influence over Arcadius and angry at his uncompromising severity against sin and vice. She became the chief instrument of his downfall.

The occasion was furnished by an unauthorised use of his Episcopal power beyond the lines of his diocese, which was confined to the city. At the request of the clergy of Ephesus and the neighbouring bishops, he visited that city in January, 401, held a synod and deposed six bishops convicted of shameful simony. During his absence of several months he left the Episcopate of Constantinople in the hands of Severian, bishop of Gabala, an unworthy and adroit flatterer, who basely betrayed his trust and formed a cabal headed by the empress and her licentious court ladies, for the ruin of Chrysostom.

On his return to Constantinople he used unguarded language in the pulpit, and spoke on Elijah's relation to Jezebel in such a manner that Eudoxia understood it as a personal insult. The clergy were anxious to get rid of a bishop who was too severe for their lax morals.

The Repose of Saint John and the Transfer of His Relics (adapted from the OCA website)

The saint died in the city of Comene on September 14th in the year 407 on his way to a place of exile, having been condemned by the intrigues of the empress Eudoxia because of his daring denunciation of the vices ruling over Constantinople. The last words on his lips were, "Glory be to God for all things!" The transfer of his venerable relics was made in the year 438: after 30 years following the death of the saint during the reign of Eudoxia's son emperor Theodosius II (408-450).

Saint John Chrysostom had the warm love and deep respect of the people, and grief over his untimely death lived on in the hearts of Christians. Saint John's student, Saint Proclus, Patriarch of Constantinople (434-447), making Divine-services in the Church of Saint Sophia, preached a sermon which in glorifying Saint John he said: "O John! Thy life was filled with difficulties, but thy death was glorious, thy grave is blessed and reward abundant through the grace and mercy of our Lord Jesus Christ. O graced one, having conquered the bounds of time and place! Love hath conquered space, unforgetting memory hath annihilated the limits, and place doth not hinder the miracles of the saint." Those who were present in church, deeply touched by the words of Saint Proclus, did not allow him even to finish his sermon. With one accord they began to entreat the Patriarch to intercede with the emperor, so that the relics of Saint John might be transferred to Constantinople. The emperor, overwhelmed by Saint Proclus, gave his consent and made the order to transfer the relics of Saint John. But the people dispatched by him were by no means able to life up the holy relics -- not until that moment when the emperor realising his oversight that he had not sent the message to Saint John, humbly beseeching of him forgiveness for himself and for his mother Eudoxia. The message was read at the grave of Saint John and after this they easily lifted up the relics, carried them onto a ship and arrived at Constantinople. The reliquary coffin with the relics was placed in the Church of the holy Martyr Irene. The Patriarch opened the coffin: the body of Saint John had remained without decay. The emperor, having approached the coffin with tears, asked forgiveness. All day and night people did not leave the coffin. In the morning the reliquary coffin with its relics was brought to the Church of the Holy Apostles. The people cried out: "Receive back thy throne, father!" Then Patriarch Proclus and the clergy standing at the relics saw Saint John open his mouth and pronounce: "Peace be to all."

In the IX Century the feast day in honour of the transfer of the relics of Sainted John Chrysostom was written into church singing.

Commemorated November 13/26

Commemorated November 13/26